In American Quarterly Volume 65, Issue 3 (September 2013), a special issue on Species/Race/Sex, we bring together scholars from various fields and at different stages in their careers to address the species/race/sex nexus from a number of disciplinary and interdisciplinary angles and ideological positions. Explore the supplementary content from this issue.

Edited by Claire Jean Kim and Carla Freccero

Having contributed profoundly to the analysis of power’s many dimensions—racism, heteropatriarchy, imperialism, neoliberalism, and more, for many decades—American Studies is well situated now to address the question of species and the nonhuman animal. It can theorize and critique the fraught relationship between the domination of nonhuman animals and other forms of domination typically addressed in American studies in powerful and creative new ways. Thus American Studies both contributes to our understanding of this relationship and benefits from expanding to encompass another vector of oppression. It has much to learn from—and to teach—the equally politically committed and analytically diverse emergent field of Animal Studies that also informs studies of domination and the nonhuman sphere.

Having contributed profoundly to the analysis of power’s many dimensions—racism, heteropatriarchy, imperialism, neoliberalism, and more, for many decades—American Studies is well situated now to address the question of species and the nonhuman animal. It can theorize and critique the fraught relationship between the domination of nonhuman animals and other forms of domination typically addressed in American studies in powerful and creative new ways. Thus American Studies both contributes to our understanding of this relationship and benefits from expanding to encompass another vector of oppression. It has much to learn from—and to teach—the equally politically committed and analytically diverse emergent field of Animal Studies that also informs studies of domination and the nonhuman sphere.

In American Quarterly Volume 65, Issue 3 (September 2013), a special issue on Species/Race/Sex, we bring together scholars from various fields and at different stages in their careers to address the species/race/sex nexus from a number of disciplinary and interdisciplinary angles and ideological positions. As issue editors, Kim and Freccero hope that the range of subjects, approaches and disciplinary perspectives offers readers both within American Studies and elsewhere inspiration to take up intersectional analyses in all their potential richness to address planetary struggles in their full complexity.

Co-editor Claire Jean Kim would like to make a special call out to several scholars and activists whose work on species/race/sex is pathbreaking and powerful, including Carol Adams, Lauren Ornelas, Pattrice Jones, A. Breeze Harper and Lori Gruen. Everyone interested in these dimensions of power and their intersections should visit their sites for information, provocation, and inspiration. The deepest respect as well to the late Marti Kheel, whose work has influenced all of us and will continue to influence future generations. Fiona Probyn-Rapsey has done tremendous work on race, nationalism, and animal slaughter in Australia, including her paper “Stunning Australia” and for the companion lecture.

Additionally, co-editor Carla Freccero includes a short list of fiction that helps craft ways to think about species, race and sex beyond standard analytic tools and provides creative ways of addressing the coarticulations of the complex beings we call the living.

- Toby Barlow, Sharp Teeth (Harper Perennial, 2008)

- Sabina Berman, Me, Who Dove into the Heart of the World, trans. Lisa Dillman (Henry Hoit and Co., 2012)

- Octavia Butler, Lilith’s Brood (Grand Central Publishing, 1989)

- Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber (stories) (Penguin, 1979)

- J.M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals (Princeton University Press, 1999)

- J.M. Coetzee, Disgrace (Penguin, repr. 2008)

- Marie Darrieusecq, Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation, trans. Linda Coverdale (The New Press, 1997)

- Karen Joy Fowler, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves (Putnam, 2013)

- Martha Grimes, Dakota (NAL Trade, repr. 2009)

- Nalo Hopkinson, Skin Folk (short stories) (Warner Books, 2001)

- Ursula K. Le Guin, Buffalo Gals and other Animal Presences (short stories) (Penguin, 1990)

- Ruth Ozeki, My Year of Meats (Penguin, 1999)

- Karen Russell, Vampires in the Lemon Grove (short stories) (Knopf, 2013)

- Karen Russell, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves (Vintage, repr. 2007)

Cockfight Nationalism: Blood Sport and the Moral Politics of American Empire and Nation Building

Janet M. Davis

The essay explores the symbiotic relationship between animal welfare and ideologies of nation building and exceptionalism during a series of struggles over cockfighting in the new US Empire in the early twentieth century. Born out of the shared experience of American overseas expansionism, these clashes erupted in the American Occupied Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, where the battle lines pitting American-sponsored animal protectionists against indigenous cockfight enthusiasts were drawn along competing charges of cruelty and claims of self-determination. Davis argues that battles over the cockfight were a form of animal nationalism—that is to say, cockfight nationalism. Cockfight enthusiasts and opponents alike mapped gendered, raced, and classed ideologies of nation and sovereignty onto the bodies of fighting cocks to stake their divergent political and cultural claims regarding the rights and responsibilities of citizenship, moral uplift, benevolence, and national belonging.

Related Links

The Animal Legal & Historical Center is sponsored by the College of Law at Michigan State University. This comprehensive and easily navigable website is comprised of contemporary and historical legal documents concerning animals in the United States and around the world: federal/state/local laws, ordinances, bills, cases, treaties, pleadings and briefs, and a compendium of secondary scholarly materials. Collectively, these legal sources illuminate the depth and complexity of human and animal interactions, as well as the myriad ways that human beings consider animals—as family members, property, metaphor, food, art, entertainment, symbol, fashion, and religious ritual.

Materia Medica: Technology, Vaccination, and Antivivisection in Jazz Age Philadelphia

Jeannette Vaught

During the 1920s, the Philadelphia-based American Antivivisection Society turned to racialized metaphors in its circulating periodical, the Starry Cross, to excoriate the expanding practice of vaccination. Since vaccines were then made from animal-derived serums, the involvement of antivivisectionists in antivaccine arguments is not surprising. However, the Philadelphia society’s strange combination of vaccination, jazz, and vivisection reveals that its motivations to protect animals were deeply bound to broader cultural anxieties about the threat to purity posed by science, race, and sex, and that the stakes of succumbing to vaccination amounted to no less than medical miscegenation. By turning to racialized, speciesist arguments in asking for mercy toward animals against scientifically minded torture, the antivivisectionists’ use of the sound and image of the tortured animal was meant more to protect the human body and keep it white.

The following links briefly overview the current strains of controversy surrounding vaccination, and represent a variety of perspectives. Contemporary vaccination debates echo the Philadelphia Antivivisection Society’s enmeshing of religion, science, and capitalism, yet animals and race have disappeared from the discussion. I suspect that, instead of vanishing completely, they have been replaced – perhaps sublimated – by the more esoteric desire for “nature” and “natural care” espoused by white antivaccination activists (a desire which nonetheless resonates with their antivivisectionist forebears). Such abstraction is a pernicious and effective erasure of still-extant historical preoccupations with whiteness and contamination.

Related Links

A YouTube video posted by The Health Ranger, which echoes the AAVS's concerns about polluting the body and using natural methods to promote health -- though the main target is now the chemicals, not animal-derived serums, used in vaccines.

A short video posted by autism activists of Temple Grandin, espousing caution but not abandonment regarding vaccines.

An informational web page put out by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia about the history of vaccines and vaccinations in the United States. This particular page addresses contemporary frequently asked questions, which lean towards individual rather than societal concerns.

A video put out by VaxTruth, a contemporary active anti-vaccination campaign. Again, while they are adamant that vaccines cause disease, the video emphasizes individual child health rather than societal anxieties (though it does reveal perceived recklessness of state control).

A blog post by an Asperger's patient detailing her experience uncovering the links between autism and race—a pretty fascinating look at the research it takes to do so, and how invisible race is to the autism-activist community in a contemporary setting. While this is a little out of range for the article, the long road one has to take to get from vaccines to autism to race is pretty interesting to think about, especially since race , animals and antivivisection have become subtractions, present but invisible behind a construct of nature, in current antivivisection activism.

Two very recent news articles detailing ongoing divisions between public health and antivaccination activists, one about a high-profile measles outbreak and another about the legal rights of non-vaccinators.

Animal Instincts: Race, Criminality, and the Reversal of the “Human”

Megan H. Glick

In 2007 Atlanta Falcons’ quarterback Michael Vick was arrested for owning and operating the Bad Newz Kennels, a large interstate dogfighting ring. As the facts of the case unfolded, Vick was publicly attacked by animal rights groups, who were outraged by the abuse perpetrated at the kennels, particularly the violent “execution” of the dogs after fighting by means of torture, electrocution, drowning, and hanging. While the term execution typically refers to the realm of human death, its use in the context of the Vick case suggests that something more than animal abuse was at stake. "Animal Instincts" uses the Vick saga to interrogate the often invisible, and often racialized, intersections of animal and human rights discourse.

Related Links

Clips from The Michael Vick Project (BET)

PETA's Involvement

On the “Glass Walls” exhibit (previously known as “Are Animals the New Slaves?”):

PETA, "Meat Equals Slavery"

PETA,“Glass Walls"

Danielle Wright, "Another PETA Exhibit Compares Animal Cruelty to Slavery"

On PETA’s Michael Vick protest:

PETA, "Vick Protests in New York City"

Video footage of PETA protest outside Vick’s trial

Dog Town: Saving the Michael Vick Dogs

Clip of Part 1, The National Geographic Channel

The “Vicktory” Dogs at Best Friends Animal Sanctuary

“What if Michael Vick Were…”

Original image accompanying the ESPN article by Touré, “What if Michael Vick Were White?”

Three notable examples of the “What if Michael Vick Were…” meme, which took off in the weeks following the publication of the original image:

What if Michael Vick…were made of barbeque spare ribs? Would you eat him?

What if Michael Vick were a Dog?

What if Michael Vick were Pitbull?

In these memes, Vick becomes a bloody mass of meat, a (black) dog, and Cuban-American rapper and producer, Pitbull. The threefold gesture of transforming Vick from person to thing and animal, and from African American to an alternate race, is suggestive of broader patterns in the cultural imaginary surrounding the case. Reversals, whether conceived of in racial terms, or across the species boundary, characterize public discourse on Vick, who is alternately envisioned as deeply racialized and post-racial, predator and prey.

The Michael Vick Chew Toy

The Official Vick Dog Chew Toy

This “official” toy foregrounds Vick’s criminality, while making no reference to his role in dog fighting; instead, the packaging simply reads: “Where’s my plea?” Others on the market include a “limited edition prison chew toy,” which features Vick in a prison-striped football uniform.

Orthodox Transgressions: The Ideology of Cross-Species, Cross-Class, and Interracial Queerness in Lucía Puenzo’s Novel El niño pez (The Fish Child)

Ángeles Donoso Macaya & Melissa González

El niño pez (The Fish Child), a 2004 Argentine novel about an interracial lesbian couple narrated by a dog, illustrates some of the central challenges and desires of animal studies, particularly those involved in overcoming humanism, sexism, and racism. By presenting the readers with a story of same-sex, interclass, and interracial coupling narrated by an eloquent pet dog, The Fish Child appears to stage a series of sexual, interspecies, and class transgressions. However, the novel instead stages a central problem of our neoliberal times: simply violating traditional boundaries and hierarchies is not inevitably transgressive of the social order but can actually represent hegemonic ideologies. Putting this Argentine novel in dialogue with Anglo-European animal and queer studies, the authors demonstrate some of the transnational commonalities and epistemological challenges of speciesism, sexism, and racism.

Related Links

The film version of El niño pez (The Fish Child), directed by the novel’s author, Lucía Puenzo, does away entirely with the dog narrator that is so crucial in our analysis of the novel. This decision by Puenzo may have been motivated by the fact that, when it comes to film, dog narrators tend to be more common in productions aimed at children than in adult dramas. This is less the case for literature, as Virginia Woolf’s Blush, Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog, and Garth Stein’s The Art of Racing in the Rain are just three of many examples of novels with dog narrators. On the other hand, while the 1955 film It’s a Dog’s Life is one of few examples of a live-action film with a dog narrator intended for adult audiences, a majority of both live-action and animated films with animal narrators or protagonists have tended to belong to the genre of the children’s or family film. Recent examples of live-action family films with talking or narrating animals include 1993’s Homeward Bound, 1995’s Babe, the 1994 remake of Black Beauty, 1998 version of Doctor Dolittle, 2001’s Cats and Dogs, 2008’s Beverly Hills Chihuahua, and 2011’s Zookeeper. Hollywood films have long dominated the Argentine box office, so we can surmise that many of these films were widely seen in Argentina as well. See Jonathan Burt’s Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002) for a history and analysis of the politics of animals in world cinema.

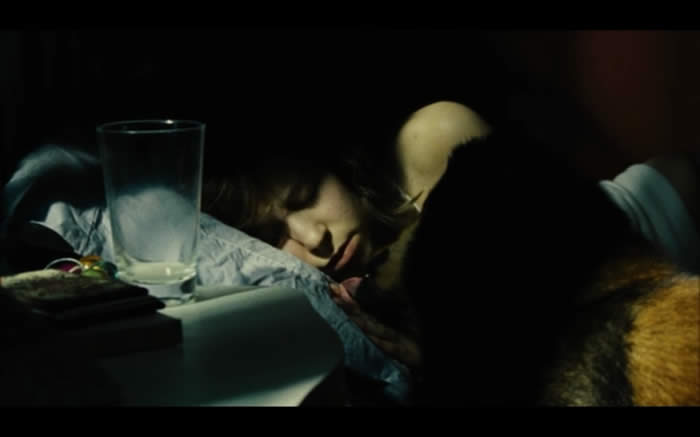

For those viewers who have also read the novel, the absence of the dog as narrator slowly comes into focus at the beginning of the film version of The Fish Child. It opens with the sounds of the dog breathing and softly whining over a black screen. The first shot shows the dog approaching and licking a sleeping Lala. It soon becomes apparent that this opening scene is set the morning after Lala drank milk with her father, unsure of which glass was the one she had poisioned, equally willing to commit suicide or murder.

Scenes recounting the aftermath of the murder of Lala’s father are intercut with the opening credits. The credits are displayed over a watery background of the lake in Paraguay where the eponymous fish child lives, cluttered with mementos and offerings left by locals who believe in the legend of the fish child.

The final shot of the credits shows a blurry CGI fish child swimming briefly across the left-hand side of the screen. In this visual representation of the fish child, he takes on the quality of reality, since all viewers of the film see him at the outset and immediately infer what the title refers to. In the novel, on the other hand, only Lala catches a brief glimpse of him midway, and she herself wonders if she is going crazy. Both the novel and the film eventually make it clear that the fish child is only a lie become legend, originally told to cover up Lin’s infanticide.

After the credits intercut with the scenes showing the aftermath of Lala’s murder of her father, the film flashbacks several months earlier to show the beginning of Lala’s romance with her family’s maid, Lin.

Any centrality suggested by the appearance of the dog at the very outset of the film is undermined by the film’s version of how Serafín joined the Brönte household, depicted immediately after the opening credits. In the film, a discarded puppy Serafín is rescued by Lin and given to Lala as a “present,” underscoring his status as mere animal accessory to their romance.

Indeed, the dog’s importance throughout the film is relatively minor, especially when compared to the novel. In the novel, on the other hand, Serafín’s objectifying, macho gaze anthropomorphically reproduces patriarchial gender roles as he sexually desires his mistresses. Interestingly, without the power of narration, the innocuous dog in the film occupies the inferior position in an entirely different hierarchy, that of human and animal.

It is also interesting to consider the ways that the film is marketed differently to different audiences, suggesting that spectacle of the lesbian relationship was assumed to be most attractive to a North American audience, while the spectacle of the fish child was assumed to be more interesting to a Latin American audience.

Here is one of several trailers intended for Spanish-speaking audiences that emphasize the eponymous fish child.

Here is a trailer for the film version of El niño pez intended for an English-speaking audience that emphasizes the lesbian relationship in the film.

Nevertheless, an English-speaking audience may not necessarily be most excited about the lesbian sex in the film. A review of the movie by Johnnie Gray on the GLBT Reviews website, authored by members of the American Library Association GLBT Round Table, argues that the film “would make a great addition to an academic or public library that desires more foreign GLBT films that don’t revolve around sex, but rather love.” Complementing this anti-sex-sounding assesment of the film’s strengths, Gray’s review also demonstrates some of the gaps in understanding that can ocurr when North Americans consume Latin American media; namely, he labels the two protagonists “Latinas” and explains their ethnic and class difference as a difference in “caste.”

“Of Course There Are Werewolves and Vampires”: True Blood and the Right to Rights for Other Species

Dale Hudson

Often dismissed as superficial, vampire films and television series have been a dominant mode by which Hollywood has negotiated the ever-shifting contours of social difference in the United States since the 1920s and 1930s. Remarkably, critical analysis has paid little attention to the interconnections between racism, sexism, and speciesism—and almost no attention to ways that difference affects nonhuman animals. Drawing on work in animal studies and the posthumanities, the article explores the extent to which HBO’s True Blood (2008–present) can contribute to the ongoing process of decolonizing thinking from the everyday habits defined by anthropocentrism. By featuring supernatural species, it questions unwitting complicity with forms of cinematic and televisual realism in reifying political realism. The series is premised on the political organization of vampires who advocate for the right to the right of citizenship, exploring ongoing asymmetries in social and political power through resurrected Confederate soldiers, ghosts of murdered women and children, and terrorism in the form of rebel vampire groups exploding the factories where synthetic blood is manufactured and multiracial hate-groups of male and female humans wearing rubber “Barack Obama” masks and murdering shapeshifters. If the animal turn follows the postcolonial turn, then this article asks whether True Blood might suggest ways for humans to live ethically with other species and to think interspecies relations in ways that consider what interspecies ethics might also mean to humans still defined in terms of race, sex, nativity, and religion.

Related Links

Like most contemporary commercial television series, True Blood is released over multiple media platforms, including a YouTube channel, which features public service announcements by the stars in character, social networking presence on Facebook and Twitter, which post updates and teasers, and an online store, which sells ancillary products such as t-shirts and DVDs.

In addition to HBO’s use of the Internet to push content to user, the network and series producers also use the Internet to interact with fans and involve them in the series’ fictional universe, particularly in terms of their views on sexism, racism, and speciesism. Since actual sentiments are indistinguishable from performed ones (users performing fictional identities as in alternative-reality games), the series’ blogs and social networking platforms foreground ways that categories of sex, race, and species are constructed through digitally mediated social interactions.

True Blood’s multiplatform narrative operates across a number of blogs that extend the fictional debate of the right to rights for other species.

The Fellowship of the Sun has been less central to the series’ narrative since earlier seasons. In addition to motivational speeches, the website performs the “public service” of publishing information on missing humans in which “vampire involvement is suspected,” inviting users to contribute. Presently, posts consist of user-contributed sightings of the missing Reverend Steve Newlin. A less genteel version of anti-vampire racism/speciesism appears on the fictional grassroots Keep America Human website with its “Human Patriot Manifesto.” The website is designed to appear as one made by the “Barack Obamas” in the fifth season. Vamps Kill features fictional amateur videos of vampire attacks on humans, some of which are used on the series itself. Actors urge viewers to post the videos on their Facebook pages, so that their message will go viral through social media.

Finally, Soldiers of the Sun offers a fictionalized recruitment video on YouTube that mobilizes the visual strategies of white supremacist and libertarian groups in the United States. YouTube users can post comments. The features of True Blood likely do not flame anti-difference intolerance as much as they parody ways that social media construct social impressions of reality in what has been described as the “post-information era” of user-contributed content as a source for commercial news media, such as hoax that prompted FOX News to report on a fictional dangerous hallucinogen made from human excrement called “Jenkem” or “ButtHash” in 2007.

American Vampire League (AVL) responds to the alarmist discourses of the above sites, particularly in terms of the destruction of TruBlood factories by assuring users that “the AVL is working round the clock with Homeland Security to bring these terrorists to justice and to restore our food supply chain.” The AVL encourages “hate-free coexistence” through a “pact” of patience, acceptance, charity, and tolerance. Babyvamp Jessica is a vlog, featuring the thoughts of the newbie vampire Jessica, which includes fictional personal data of social networking such as the information that Jessica is currently listening to Taylor Swift, reading The Hunger Games and Fifty Shades of Grey, watching I Didn’t Know I Was Pregnant and I Shouldn’t Be Alive, and drinking “O Neg, neat, up.” These features of True Blood seek to normalize species difference.

Online debates about the series extend from HBO’s licensed sites for fans to academic forums, such as FlowTV and InMediaRes, where the series’ emphasis on the supernatural difference as a means of addressing social differences of sex, race, and species is often considered.

In “Vampire Politics,” Lisa Nakamura, Laurie Beth Clark, and Michael Peterson suggest that the series’ evocative opening credits sequence, designed by the branding agency Digital Kitchen , creates expectations for substantive analysis of the place of race, sex, and species that remain unfulfilled in the narrative episodes. “True Blood is socially conservative, gesturing towards a radical politics (or any social movement based politics) that it cannot (or will not) deliver,” they argue; “Likewise, the form of the medium itself is conservative. Like its vampires, True Blood is a relic — it airs on television, not the Internet, and it is broadcast rather than streamed.”

In “Buffy Failed: True Blood and the Accommodation of Vampires,” Jon Stratton challenges the assumptions on the series’ interest in exploring the legacies of racism and its use of the Internet as part of its platform. He examines a fan post on the Fangtasia Forums around the casting of the vampire Chow by a “rather portly Patrick Gallagher” in the role of a character described in the Sookie Stackhouse novels as “friggin hot… covered in Yakuza tattoo’s (sic) with long black straight hair.”

Comparably, in “Defictionalization,” Lisa Patti examines the series’ use of its online store to push its narrative into the everyday realities of its fans by “defictionalizing” a blood-orange–flavored soda that is sold as TruBlood. Patti analyzes an advertisement for the soda as appealing primarily to male audience through the familiar tropes of beer advertisements. In many ways, her analysis of the fictional advertisement reveals ways that the series reproduces the centrality of white-male-human identity in its episodes, blogs, and social networking by not substantially addressing the social and material consequences of sexism, racism, and speciesism in the contemporary United States.