The September 2011 special issue featured a wide range of scholarly thinking on sound—from nineteenth century noise ordinances to the abstract beauty of sound to the relation of Johnny Cash to Native American soundscape—and signal to the readers of AQ of the critical role of sound in the broad field of American studies. This page includes supplementary content from several articles.

Edited by Kara Keeling and Josh Kun

Music studies have long been fundamental to American studies, but sound—and the sensuous acts of listening and hearing—have just recently been attracting a wide range of scholarly attention. The ability to generate sonic matter—to listen, to hear some sounds and not others—involve practices and forms of labor, as the editors note in their introduction, that engage in and revolve around relations of power. These power relations enforce certain kinds of inclusions and exclusions, involving gender, race, class, sexualities, and other formulations of identity, points of contact, and instances of conflict. Sound is understood in this issue as a cultural form with a material force and the studies here occasion examinations into the sonic and aurality as processes of economic, social, and political negotiations.

View the Table of Contents. Authors who contributed supplementary content appear alphabetically below.

"Abolitionism’s Resonant Bodies: The Realization of African American Performance," Alex W. Black

"Audible Citizenship and Audiomobility: Race, Technology, and CB Radio," Art M. Blake

"Marian Anderson and 'Sonic Blackness' in American Opera," Nina Sun Eidsheim

"The 'War on Noise': Sound and Space in La Guardia’s New York," Lilian Radovac

"'What, for me, constitutes life in a sound?': Electronic Sounds as Lively and Differentiated Individuals," Tara Rodgers

"Intimacy Threats and Intersubjective Users: Telephone Training Films, 1927–1962," D. Travers Scott"The Political Agency of Musical Beauty," Barry Shank

"'An Indian in a White Man’s Camp': Johnny Cash’s Indian Country Music," Dustin Tahmahkera

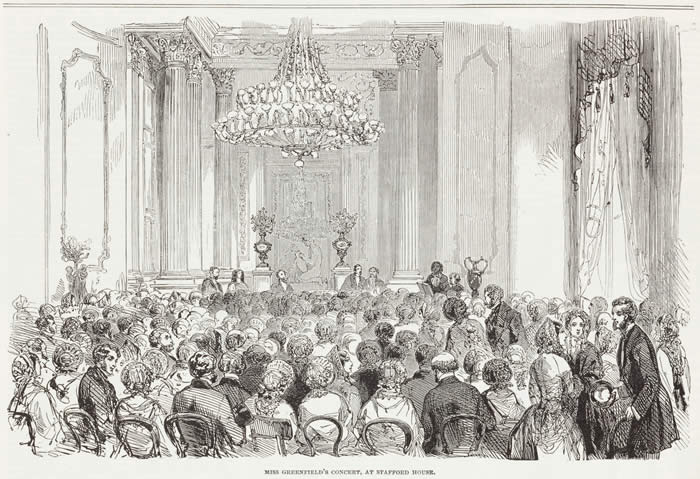

Abolitionism's Resonant Bodies: The Realization of African American Performance

Alex W. Black

This essay contributes to the study of early African American performance by exploring how that performance archives itself and by investigating the work that that archive performs. It appreciates that "African American expressive culture and artistic production" form a tradition in which "sound and vision, the aural and the scriptural, have always been interlinked."

Elizabeth Greenfield, The Black Swan. The Illustrated London News, July 30, 1853. Courtesy of the Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

Mary Webb, The Black Siddons. The Illustrated London News, August 2, 1856. Courtesy of the Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

Audible Citizenship and Audiomobility: Race, Technology, and CB Radio

Art M. Blake

Black CB shows how "community" and "identity" do not necessarily originate through direct contact and communication. Its users built on an already existing black aural public sphere—rooted in black-interest radio, jive talk, and jazz and blues lyrics—and adapted CB technology to combine with that aural-oral sphere to connect geographically and socially diverse individuals. Black CB thus indirectly created a technologically mediated community based on perceived audible racial identity.

Marian Anderson and "Sonic Blackness" in American Opera

Nina Sun Eidsheim

On a cloudy January 7 in 1955, the golden-red auditorium glowed with expectation. On the dark, gaping stage beyond the proscenium, Marian Anderson took her position as the gypsy sorceress Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera. The emotional power of this moment is not surprising. At the time of Anderson's debut, the Metropolitan Opera, the largest and most prestigious opera house in the United States, had been exclusively white for its entire seventy two- year history. Most people felt in 1955 that despite her brief tenure (only eight performances over two seasons) Anderson's hiring was a decisive moment on the path toward desegregating classical music; it was celebrated as a new chapter in American racial relations and policies. Many of the conditions that Anderson had to overcome to reach this pivotal moment gradually improved for later generations of African American singers. However, while the second half of the twentieth century saw American opera houses decisively integrated, the black performer is yet consistently viewed as peculiar. While descriptions of her visual appearance have been toned down through the decades, the timbre of her voice has routinely (if often admiringly) been characterized as "black."

Recordings available online

- Marian Anderson; Dimitri Mitropoulos: Un Ballo in Maschera, Re dell'abisso, 2:06

RCA Victor LM-1911; MET 220CD Portraits in Memory: Marian Anderson

http://www.metoperafamily.org/metopera/history/sounds/player.aspx?t=97

- Leontyne Price as Aida, her last Metropolitan Opera performance (1985), is available to view using the Met Player Video. (Registration may be required.)

http://www.metoperafamily.org/met_player/catalog/detail.aspx?upc=811357011799

Other suggested recordings

- Four Saints in Three Acts (original cast): Thomson, Virgil. Four Saints in Three Acts. (Abridged by the composer.) Starring Beatrice Robinson-Wayne, soprano, and Edward Matthews, baritone, with supporting soloists, chorus, and orchestra, the composer conducting. Recorded 1947. BMG 09026-68163-2. 1996, Compact disc.

- Porgy and Bess (original cast): Gershwin, George. Porgy and Bess. Selections. Recorded 1942. MCA Records MCAD 10520. MCA 1992, Compact disc.

- Simon Estes as the Flying Dutchman (Wagner, Richard): Der Fliegende Holländer; from the Bayreuther Festspiele 1985. DVD. Composed by Wagner, Richard; directed by Harry Kupfer, 1985. Hamburg: Deutsche Grammophon.

- Leontyne Price as Donna Anna: Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus. 1960. Don Giovanni: RCA Victor. LM 6410

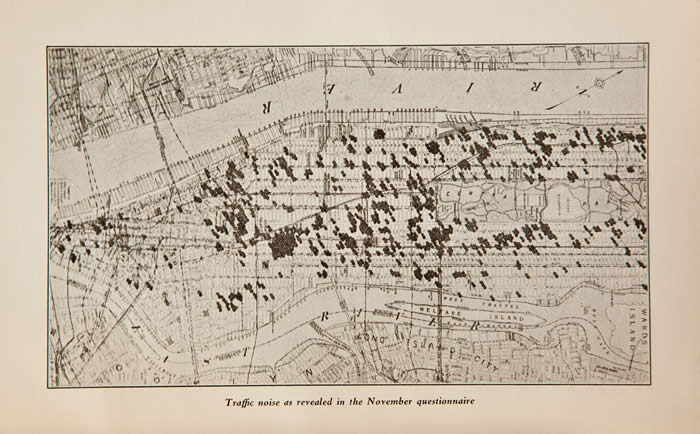

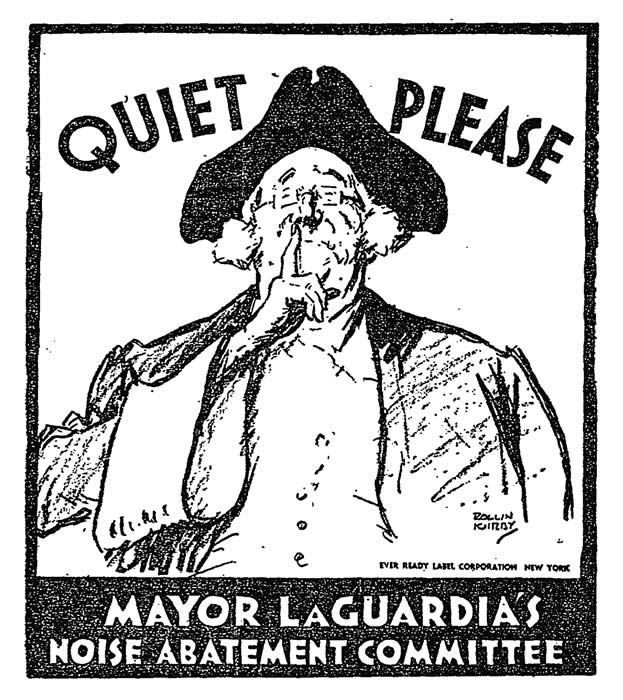

The "War on Noise": Sound and Space in La Guardia’s New York

Lilian Radovac

On December 4, 1939, a couple brought a noise complaint before the New York City courts. The Lewises, who resided at Fourteen Sutton Place South and were known within society circles, filed charges against the Merritt-Chapman and Scott Corporation for allegedly violating the city's antinoise ordinance. At the time of the Lewises's case, New York City was in the midst of a "war" on noise, which had commenced in 1935 and was waged by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and his police commissioner, Lewis Valentine, for the rest of the decade and half of the next. Still hobbled by the Great Depression but also firmly entrenched in a period of rapid and, for some, brutal revitalization, the city brought sound to the forefront of a wide-ranging campaign to rehabilitate, reorganize, and transform urban life.

"Traffic noise as revealed in the November questionnaire," visually represented in a noise map produced by the Noise Abatement Commission. Edward Brown et al., eds. City Noise. (New York: Department of Health, 1930), 30.

New York's Father Knickerbocker was enlisted to aid La Guardia's antinoise drive, calling for "Quiet, Please!" in this promotional campaign. In Fiorello H. La Guardia, "Noise Abatement Campaign: Miscellaneous Press Releases," (City of New York: Office of the Mayor, 1935). Courtesy New York Public Library.

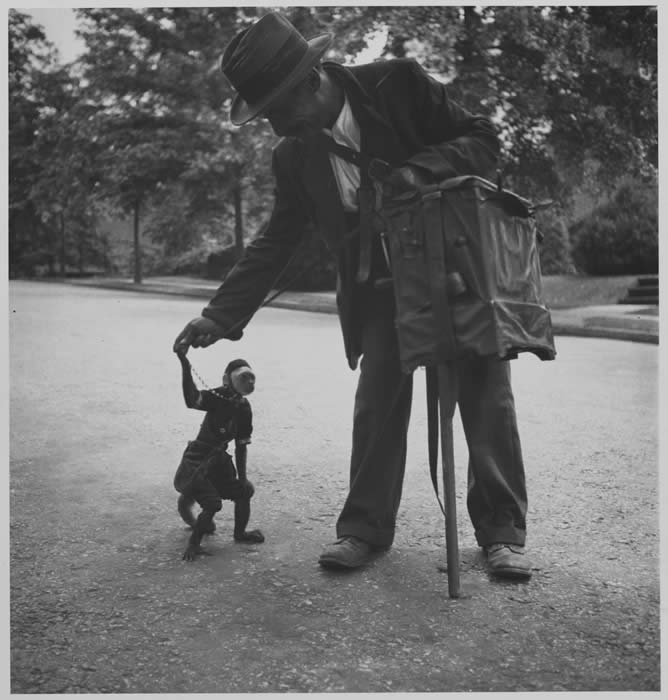

One of the last organ grinders legally permitted to perform in New York City. Photograph by Samuel H. Gottscho. "Organ Grinder and Monkey, Washington Heights." (New York, NY: 1935.) Courtesy Museum of the City of New York, Gottscho-Schleisner Collection. 58.62.7.

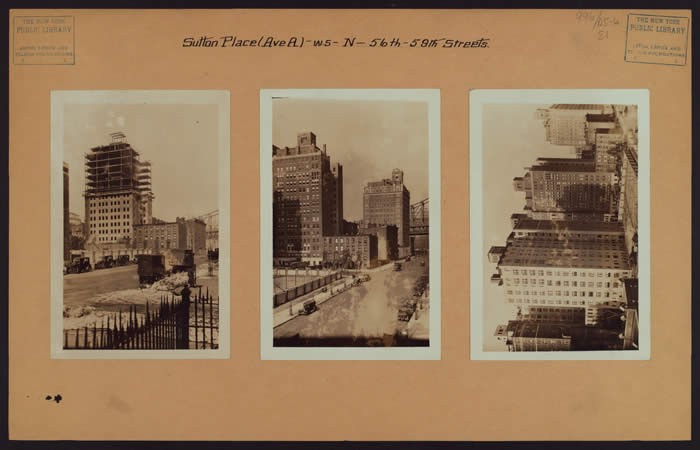

The view from the corner of 56th Street and Sutton Place South, the location of the Lewises' luxury apartment house, during the real estate boom of the late 1920s. Photograph by Percy Loomis Sperr. "Manhattan: Sutton Place - 56th Street." Photographic Views of New York City, 1870s-1970s / Manhattan. (New York, NY: 1927; 1928.) Courtesy Milstein Division of United States History, Local History & Genealogy, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. 723484F.

"What, for me, constitutes life in a sound?": Electronic Sounds as Lively and Differentiated Individuals

Tara Rodgers

As graphical methods were adopted across scientific disciplines in the nineteenth century, sounds came to be known and understood in analogous ways to modern bodies and subjects: as differentiated individuals in motion, marked and regulated by waveform representations of their extensions into space and variations over time. The identification of electrical activity as an animating presence in a range of phenomena--from muscle movements to growing plants to new communication technologies--also facilitated analogies among electronic sounds and lively bodies. In both physiology and acoustics, curvy waveforms came to symbolize life and lively variation, compared with the flatline of stillness, death, and silence.

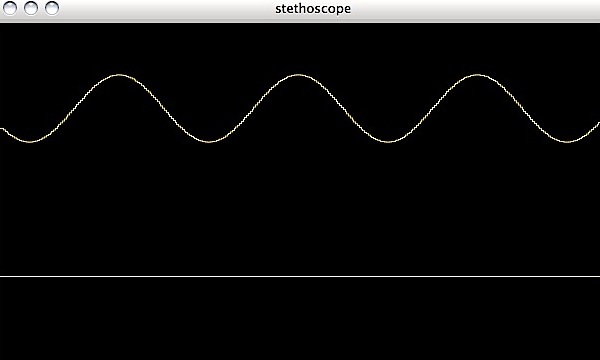

One particular curve, the sine wave, became associated with aesthetic purity, neutrality, and musical/cultural value. Descriptions of the sine wave as "pure" and "lacking body" persist in contemporary acoustics textbooks and philosophical treatises on sound. I locate the roots of this idea in Hermann von Helmholtz's neoclassical aesthetics, which articulated the sine wave to connotations of whiteness, scientific objectivity, and cultural value. By contrast, timbral variation came to signify marked forms of embodiment (e.g., raced, gendered, classed), and aperiodic waveforms represented noise--increasingly a symbol of social and cultural transformations in the modern American city, a sign of urban disorder, and a target of progressive noise abatement campaigns by the early twentieth century. The shapes of sound waveforms, as these examples suggest, are entwined with histories of scientific determinations of bodily difference and intersecting desires for social ordering and control.

A graphical representation of a sine wave oscillator (above) and silence (below), shown in the open-source software environment SuperCollider. Note that the tool in SuperCollider for displaying waveforms is named "stethoscope," like the analogous medical instrument for revealing the sounds of bodily interiors.

The sound of a sine wave, often described as the "most pure tone" and "lacking body."

A graphical representation of noise

Noise: a sonic signifier of disorder, compared with the relative purity of the sine wave.

Intimacy Threats and Intersubjective Users: Telephone Training Films, 1927–1962

D. Travers Scott

Drawing on approaches from the interdisciplinary conversations of sound studies, this essay explores a historical role of a sound technology, telephony, in assessing desirable people, especially ideal and sanctioned consumers, as conveyed by instructional films from the 1920s to the 1960s: "Now You’re Talking," "How to Use the Dial Phone," "Dial Comes to Town," three "Operator Toll Dialing" shorts, and "Century 21 Calling." They range from three and a half to twenty minutes, and all except "Now You’re Talking" were produced by or with American Telephone and Telegraph. I examine their common visual and sonic representations of telephonic experience, particularly the avoidance of intersubjective intimacy, and argue this relates to maintaining social hierarchies.

NOTE: The first two films are silent.

The Political Agency of Musical Beauty

Barry Shank

The experience of musical beauty can reinforce already existing political communities with familiar sounds and a seemingly coherent and regular resolution of tension. This musical conservation of existing community is the work of anthems, and it is the object of much traditional ethnomusicological and popular music study. More interesting for me, however, is the work that musical beauty performs when it moves beyond the intentions of its creators and outside the preformed identities of its fans. I am interested in how the experience of musical beauty complicates the experience of group identity as well as confirms it.

Here is a music video created to promote Moby's "Natural Blues." Note the extra layer(s) of meaning added by the visual narrative, which could stimulate a number of contrasting close readings.

This is Vera Hall singing "Trouble So Hard." This is the version that Alan Lomax recorded during his "southern journey" in 1959. Stripped of Moby's techno and freed of the echo layered on her voice, you can hear more clearly her breath, her controlled vibrato, and her focus.

"An Indian in a White Man’s Camp": Johnny Cash’s Indian Country Music

Dustin Tahmahkera

There are, however, multiple interpretative routes for entering the sound of Indian when encountering it in Cash’s Bitter Tears cover of LaFarge’s "Drums." Whereas the Indian in the hills "has gone berserk" in "Kaintuck," most of the Indians in "Drums" are, Cash sings, "beyond the mountains," on their allotments, reservations, and other lands in Indian Country. "Drums" is a first person Indian student's account of "survivance," or Gerald Vizenor's merged keyword for survival and resistance, from the U.S. government assimilation, or cultural genocide, policy of sending Natives to Anglo-run boarding schools in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to immerse them in "the sounds of 'civilization.'"