September 2017 - Special Issue

Edited by Chih-ming Wang and Yu-Fang Cho

This special issue presents a wide range of critical scholarship that considers the importance of the “Chinese factor” in the global imaginaries of American studies. It extends American studies to concerns with distant frontiers and borderlands in Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific, and with the undercurrents of competition and collusion between empires, past and present. Whereas the forums provide a rich set of conversations on topics ranging from transwar and transpacific history and politics, to the imagination of Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the roles of the Chinese students and China in US-China contention, the articles articulate a diverse array of methodologies and practices for reorienting American studies to the rise of China as both an opportunity and threat, informed by the complex and intersected history of imperialism, Orientalism, and neoliberalism. The film review puts a nice touch on the special issue by introducing the genre of “going abroad” films that challenge the “America in Chinese hearts.”

The Chinese Factor: Reorienting Global Imaginaries in American Studies

Chih-ming-Wang and Yu-Fang Cho

Intending to facilitate critical conversations between transpacific studies, native Pacific studies, and inter-Asia critique to confront the threat of imperialism, this special issue hopes to intervene in the global turn in American studies by putting frontier and borderland back in the center of political and cultural imaginations of imperialism. By foregrounding Taiwan as a US-China frontier and borderland, we intend to suggest that American studies scholars must come to grapple with the inconvenient truth that US imperialism constructs China as its double—as a competitor, a collaborator, and a rival—and what is considered “Chinese” today is more amorphous than the nation-state wishes to contain. We hope to develop a relational comparativist approach to understanding China and Chineseness in the folds of transpacific entanglements where issues of indigenous sovereignty, refugee migration, and settler colonial history are significant to what American studies means here and now.

Provided below is a list of books, films, archives, and websites that addresses the Chinese factor in the transpacific, inter-Asian, and native Pacific contexts. While the list is not comprehensive, it hopes to offer a fine inventory of critical tools for engaging with the complexities of our time and space, in and outside the United States.

On Taiwan as emerging out the dynamic entanglements between China and the US, Hsiao-ting Lin’s Accidental State: Chiang Kai-shek, the United States, and the Making of Taiwan offers a useful guide to this complex history with important references to the long forgotten George H. Kerr. Readers interested in US-Taiwan relations should also familiarize themselves with such legal frameworks as the Taiwan Relations Act (1979--) and the Mutual Defense Treaty between the US and the ROC (1954-1978). Information about George H. Kerr’s life and politics can be found in Correspondence by and about George H. Kerr (in Chinese) edited and compiled by Su Yao-Chong (蘇瑤崇) and published by Taipei City, Taiwan. Kerr’s most important and famous books are Formosa Betrayed and Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Whereas the former is held by the pro-Taiwan independence camp as a testimony to the 228 Uprising of 1947 that sowed the seed of Taiwan independence movement, the latter was a testament to Kerr’s scholarly effort to justify the US occupation of the Ryukyus, now known as the Okinawa Prefecture of Japan. Adam Kane’s film (2009) that features the US involvement in Taiwan’s democracy movement, also borrowed Kerr’s title. Archives related to Kerr—including his reports, notes, press summaries, clippings and writings related to Taiwan and Okinawa—can be found in the 228 Memorial in Taipei, the Hoover Institution Library at Stanford (Stanford Socrates Catkey: 4086394), the University of the Ryukyus, and Okinawa Prefectural Archives, Japan. For a good account of Kerr’s biography and what is in stock of the Okinawa Prefectural Archives, see Su Yao-Chong’s article “Introduction to Materials Related to Taiwan and Life of G. H. Kerr in Papers of Okinawa Prefectural Archives” (in Chinese). Aris Teon’s “The 228 Incident—The Uprising that Changed Taiwan’s History” (blog) offers a brief but useful account of the 228 Uprising and its implications in Taiwan today.

On the importance of frontier to US imperialism, Frederick Jackson Turner’s The Frontier in American History is worth revisiting, but his account would be better if accompanied and complimented by the scholarship on US settler colonialism and racial capitalism: for instance, Alyosha Goldsten (ed.), Formations of United States Colonialism; Bethel Saler, The Settler’s Empire; Candace Fujikane and Jonathan Okamura (eds.), Asian Settler Colonialism; Yu-Fang Cho, Uncoupling American Empire: Cultural Politics of Deviance and Unequal Difference, 1890-1910; and Iyko Day, Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism. On the concept of the borderlands, we relied on Gloria Anzaldúa’s classic Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza, because it established a paradigm-shifting understanding of the history of cross-cultural currents. For a useful clarification of the two concepts, Amy Kaplan’s essay, “’Left Alone with America’: The Absence of Empire in the Study of American Culture” is not to be missed, so are the distinctions made by Pekka Hämäläinen and Samuel Truett in their article “On Borderlands.”

Moving from Taiwan and the question of frontier/borderlands, this special issue particularly hopes to build on the field of transpacific studies that was pioneered by such luminary titles as Asia/Pacific as a Space of Cultural Production edited by Rob Wilson and Arif Dirlik, Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism edited by Elaine Kim and Chungmoo Cho, Arif Dirlik’s What Is in the Rim?, and most recently Lisa Yoneyama’s Cold War Ruins: Transpacific Critique of American Justice and Japanese War Crimes and Transpacific Studies: Framing an Emerging Field edited by Janet Hoskins and Viet Nguyen by bringing it into productive dialogues with Asian American studies and native Pacific studies. Such titles as the 2015 American Quarterly special issue on “Pacific Currents” edited by Paul Lyons and Ty P. Kawika Tengan, Epeli Hau’ofa’s We Are the Ocean, and Pacific Alternatives: Cultural Politics in Contemporary Oceania edited by Edvard Hviding and Geoffrey White are especially relevant to our effort. Readers interested in the transpacific indigenous connections may also refer to Amerasia 2015 special issue on “Indigenous Asias” and Anita Chang’s documentary film Tongues of Heaven. In Asian American studies, efforts to engage with the transpacific paradigm are entangled with a critique of US military empire: for instance, Setsu Shigematsu and Keith Camacho (eds.), Militarized Currents, Jodi Kim’s Ends of Empire, Grace M. Cho’s Haunting the Korean Diaspora, Eleana J. Kim’s Adopted Territory, as well as Ji-Yeon Yuh’s Beyond the Shadow of Camptown are not to be missed. Yến Lê Espiritu’s Body Counts: The Vietnam War and Militarized Refugees, Mimi Nguyen’s The Gift of Freedom, Sucheng Chan’s The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation, and Viet Nguyen’s Refugees and Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the War of Memory importantly enriched and complicated transpacific projects with Southeast Asian stories of refugee migration. Readers who are interested in how transpacific Asian American studies intersect with inter-Asia critique can refer to the 2012 Inter-Asia Cultural Studies special issue on “Asian American Studies in Asia” edited by Chih-ming Wang and Kuan-hsing Chen’s Asia as Method.

In the transpacific passage to imperial contention, China is a critical player. Our special issue thus engages with the rise of China discourses by introducing the “Chinese factor” as a critical lens into the story of China’s entanglement with the world through its military, economic, and diplomatic maneuvers. Minqi Li’s The Rise of China and the Demise of Capitalist World Economy, Ho-fung Hung’s The China Boom: Why China Will not Rule the World, Giovanni Arrighi’s Adam Smith in Beijing, and Martin Jacques’s When China Rules the World provide prominent and critical debates on this topic. Interested readers should extend from this critical literature to such debates on China’s presence in Africa, as documented in “China in Africa,” a new column in the BBC, and the “China Africa Project” (website), and the cultural research on Africans in China, such as the short film “African Dreams in Guangzhou” (documentary) and Robert Castillo’s V-Blog “Africans in China”, as China seeks to expand its influence through the One-Belt, One-Road Initiative. A recent film named Wolf Warrior 2 timely represents the contemporary Chinese view of Africa and its nationalist ethos that may be alarming to both Chinese and American critics. This film is by far the most gross blockbuster in Chinese cinema.

Interestingly, while China is fast becoming a global power, the Chinese cinema is still producing films that showcases the Chinese complex of America. From Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China, Frant Gwo’s My Old Classmate to Xue Xiaolu’s Finding Mr. Right I and II, going-abroad films have been a distinct footnote to China’s rise, as it strives to both become and overcome the US.

Below, some of our authors have extended their contributions, added provocative tangents and assembled other useful sources that inspire their own work.

Collective Statement on Taiwan Independence: Building Global Solidarity and Rejecting US Military Empire

Funie Hsu, Brian Hioe, and Wen Liu

The following collective statement on Taiwanese independence and the historical relation between Taiwan and America was originally made public on medium.com on February 21st, 2017, following the phone call which took place between American president Donald Trump and Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-Wen which took place on December 2nd, 2016. To view the current list of signatories and sign the statement, please visit here.

Photo credit: Rhododendrites/Creative Commons 4.0

TPP at the End of the Line: A Briefing on Economic Cooperation and Capacity Building

Arnie Saiki

The Intersection between Trade and Militarization is a very busy corner from Imi Pono on Vimeo.

"The Intersection between Trade and Militarization is a very busy corner"

"The Intersection between Trade and Militarization is a very busy corner," was from a presentation commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement at the University of California, Berkeley, sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee, Western States Legal Foundation; Working Group for Peace and Demilitarization in Asia and the Pacific; San Francisco Bay Area Chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility; Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies Program, Department of Ethnic Studies, University of California at Berkeley.

I’m just going to come out and say that despite all the cautionary fears against China’s global motivations, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) may be the most ambitious development project in the history of the world. The BRI (also known as the One Belt One Road) seeks to develop infrastructure that links China with the other regions, creating opportunities for trade and development that not only bridges the advanced economies like the EU with China, but is also inclusive of developing regions in Africa and the Pacific where opportunities for trade and development have been largely stunted as a result of economic cooperation policies adopted long before the immediate anti-communist post-World War II era.

Generally speaking, our geopolitical literacy is more apt to view the world through the lens of militarized hegemony than through trade and development, even though the outcomes benefit the same postcolonial adherents. To fully appreciate the opportunities that the BRI presents, we have to readjust that lens and focus on the access to trade, investment and development. The advanced economies (the old colonial administering powers) have used foreign aid as a tool to transfer capital, goods, and services to cooperating countries, relying upon the carrot and stick principle of development assistance in exchange for its strategic economic partnership. In contrast, in what Xi calls a “win-win” approach to trade and development, what the BRI offers is infrastructure support to provide governments and regions with greater access and security in international trade, predicated on a new kind of multilateralism, rather than it being contingent upon how it participates in the free market.

When we consider that the Silk Road began during the Han dynasty (207 BCE - 220 CE) and continued well into the 19th century, we begin to get a glimpse of how historical supply chains informs our geopolitical narrative. Caravans trading across the vast landscape provided a level of exchange in markets that grew into multicultural centers where culture, language, and belief systems mixed and thrived. The emergence of the European dominated maritime trade in the 16th century, however, replaced much of the land-based transport of goods along the Silk Road, and many of the old centers of trade were sidelined when populations moved to centers with maritime access.

As colonial powers competed for domination, islands became strategic locales for controlling maritime trade and transit points as they were easy to defend and administer. This shift from land to sea advanced the social and economic growth of maritime regions while stagnating innovation and commerce along the land-based routes.

It is within this context that the Belt and Road Initiative steps to the front of the line, altering the geopolitical map. To be clear, however, it is not as if China cut in front of the U.S., rather, it appears as if President Trump has dragged the U.S. out of the line, altogether. Since his tenure, Trump has alienated alliances, fractured agreements, and generally undermined the United State’s credibility for stabilizing the geopolitical order, and while there are other alliances altering this map, it is likely that the Belt and Road Initiative will be filling this void.

Some Consequences of the Pivot to Asia

Andrew Ross

Ping Pong Diplomacy vs. Twitter Psychosis

As dramatis personae, Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump are a well-matched pair, each vying for the lead role of the blustering vaudevillian man-child. But, however grievous, the showdown with North Korea and its leader is best seen as a sideshow act. The more serious drama is unfolding through Beijing’s strenuous but faltering efforts to defuse the human time-bomb that sits in the Oval Office.

Trump doesn’t really do détente, and so China-watchers have been counting the days until he broke the uncertain truce declared at his Mar-a-Lago meeting in April with Chinese premier Xi Jinping. The cease-fire must have required preternatural self-control on his part to desist from bashing China, one of his favorite bully targets. Remarkably the moratorium (no doubt recommended by the remnants of the State Department’s senior staff) held up for the best part of three months, which is arguably the equivalent of three years in Trump-time, though, of course, it is no match for the four decades of peace earned by Nixon’s 1972 visit to China.

By mid-summer, Trump had reverted to form by scolding Beijing for being soft on North Korea. A July 29th tweet lambasted his “foolish” predecessors who had “allowed” the Chinese” to make hundreds of billions of dollars a year in trade” while Beijing did “NOTHING” to rein in Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions. Uncharacteristically, Chinese state media responded with a direct slap; the president’s “emotional venting,” it was suggested, was no substitute for “foreign policy.” Subsequently, secretary of state Tillerson was obliged to amp up the volume by raising the prospect of “open conflict,” even though the threat was phrased more diplomatically through the suggestion that U.S.-China relations were at crossroads, after “a long period of no conflict.”

The next step on the cards is an official investigation into China’s allegedly unfair trade practices. The first targets are intellectual property violations, with currency manipulation and protectionist tariffs (staples of Trump’s election campaign) almost sure to follow. A trade war looms in the near distance, though Tillerson’s language was more ominous yet. Indeed, few would bet heavily against an armed face-off between the two powers in the East China Sea, or around the contested islands in the South China Sea. The ham-handed efforts of the Trump family, and its hangers-on, to profit from ties to interested Russian parties has occasioned a Congressional backlash, redolent of the most paranoid Cold War reflexes. Will Trump’s rants also result in the partial restoration of the pre-Nixonian status quo?

Perhaps, but this will not be out of line with the “pivot to Asia,” launched during the first Obama administration under the State Department helm of none other than Hilary Clinton. This policy, expressed designed to contain China’s influence, has not recorded much success, and was weakened further by the collapse of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade treaty. But it has bequeathed a highly militarized perimeter of bases that encircle China. From Beijing’s perspective, the U.S. solution to the “Pyongyang problem” presents the alarming prospect of a united Korean peninsula with a build-up of American troops and missiles on China’s border. The Obama-Clinton policy of pouring the “arsenal of democracy” into the region has increased the odds that a diplomatic blunder from a sitting president (100% certain in Trump’s case) will balloon into a state of direct belligerence between the U.S. and Chinese military.

The Problem of Study: China in American Studies and the Materials of Knowledge

Sharon Luk

My forum contribution shares an introductory approach to situating the place of China in American studies, with methodological emphasis on the materiality of discourse and the interlocking of (racial) ideological and geopolitical formation in battles over modern civilization. I end by suggesting that we imagine the evolution of Chinese intellectual tradition in the West as grounded in the historicity of the ultimately nameless and traceless early migrants no one will ever “know,” and I highlight new theoretical horizons that can open out in this regard. Moving deeper into the latter direction, this blog post offers a way to grapple with the meaning of ethnic heritage and links to my book, which further examines the culture of study innovated by Chinese migrants in California through the creation of “paper families” around the turn of the twentieth century.

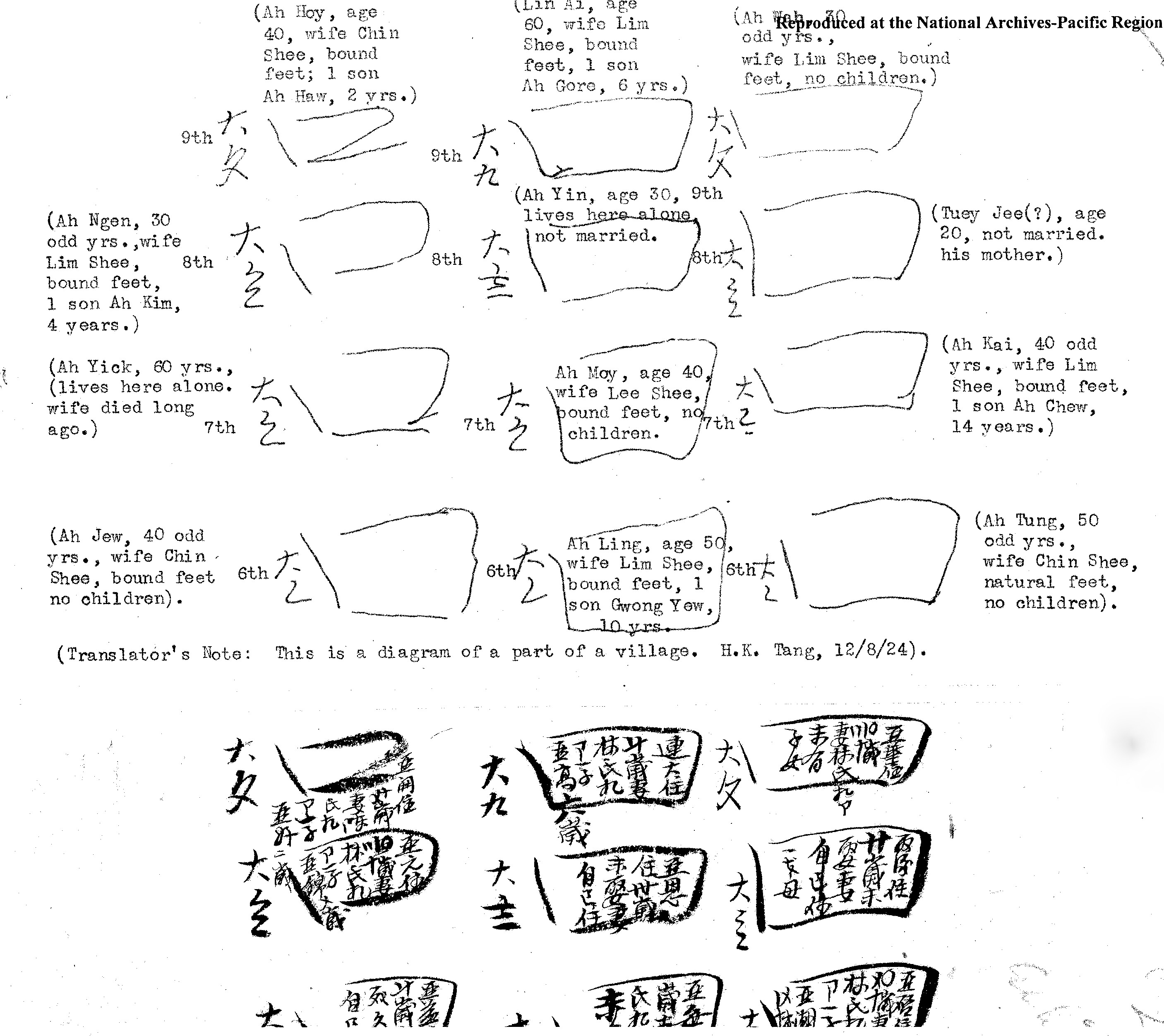

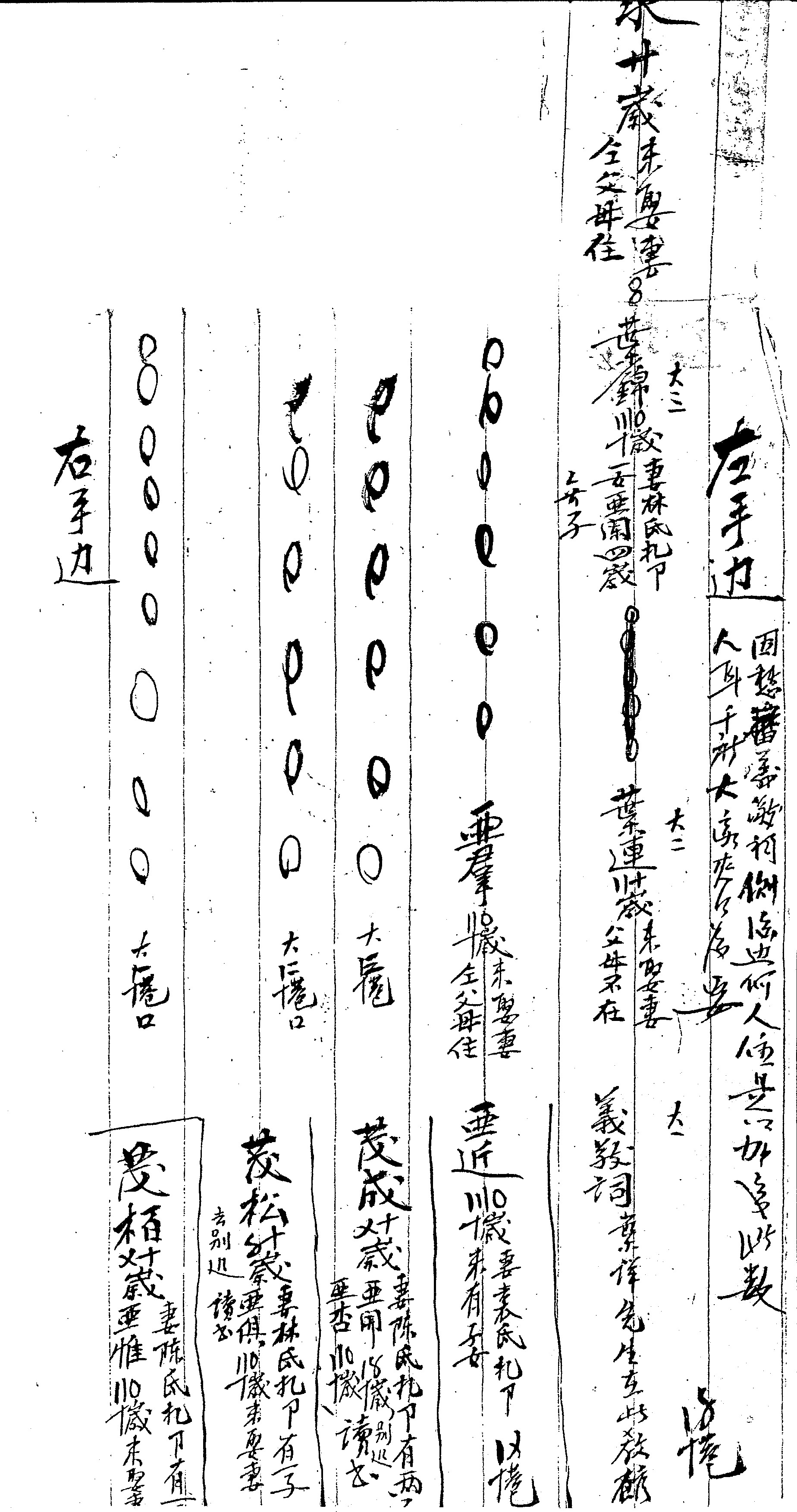

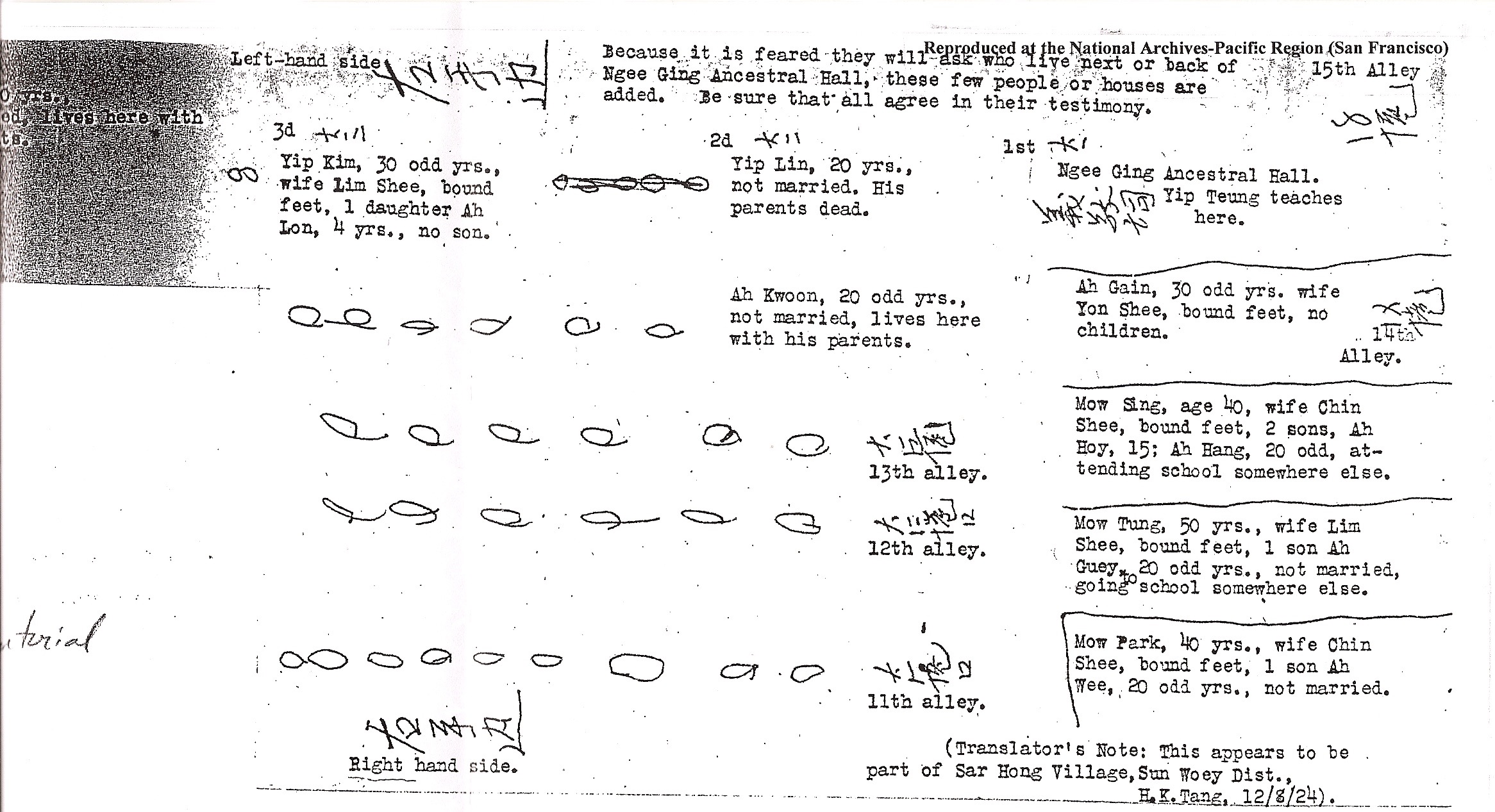

Existing work in Chinese American historiography and literature has passed on eye-opening stories about reformulations of kinship inaugurated by paper families and the surrounding context for their unfolding, including Madeline Hsu’s work on transnational sojourning, Adam McKeown and Erika Lee’s work on global U.S. immigration practices, Estelle Lau’s focused attention on paper families, Tung Pok Chin’s autobiography as a paper son, and Fae Myenne Ng’s fictional representation of lived experience. In this vein, my own research on this topic provides sustained engagements with archival documents such as the ones shown here—epistolary remnants of the composition of paper families, or letters intercepted and preserved by U.S. law enforcement agencies originally charged with controlling the situation.

Figure 1. Coaching letter, ca. 1924 (translation by Immigration interpreter H. K. Tang and original letter); Folder 6 of Box 1, Entry 232; Densmore Investigation Files, RG 85; National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (SF).

Figures 2 and 3. Coaching letter, ca. 1924 (original letter and translation by Immigration interpreter H. K. Tang); Folder 6 of Box 1, Entry 232; Densmore Investigation Files, RG 85; NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

Returning, then, to the arguments presented in “The Problem of Study,” further attention to the historical, geopolitical, aesthetic, and epistemological dynamics that animate the invention and reproduction of Chinese paper families instantiates one way to practice the approach to the problem of study and the place of China in American studies that I propose in the article. Moreover, committed investigation of this lifeworld exemplifies the alternative grounds for understanding modern forms of intellectual and social life and subjectivity that I insinuate at the article’s conclusion: elaborating forms of being that, of ultimate concern, cannot be subsumed by the forces of domination that condition them.

“Frontier Risk” and the Sino-American Scramble in the Sahel

Eric Covey

My essay examines two mercenary narratives set in Africa that explore the fate of formerly sanctioned agents of state once they fall out of favor. First, I outline the involvement of Erik Prince, the former CEO of Blackwater, with Chinese investors in South Sudan, a risk-filled venture that has raised much alarm among commentators in the United States. Next, I turn to the novel Blue Warrior (2014), in which Troy Pearce, a former CIA operative turned private military contractor, clashes with the Chinese in Mali. My comparative analysis of the cultural work of these mercenary narratives helps illuminate some of the power dynamics at work in African spaces from which both Chinese and American investors seek to extract profit. My analysis also reveals how a persistent militarism and racialized nationalism in the United States have served to cast this all as a new “scramble for Africa.”

Mali & South Sudan

One area that my essay glosses over to some degree is the relationship of the United States and Mali—the setting of Blue Warrior—during the war on terror. One of Pearce’s allies in the novel is a Tuareg from northern Mali who is cast in the same heroic manner that the mujahideen in Afghanistan were presented by the CIA and others after 1979. The 2012 Tuareg uprising in Mali is of course closely connected to the events of the Libyan civil war in 2011, when the United States suddenly reversed course and supported the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, who had cooperated with the United States beginning in 2003. While this context for the cooling of US-Malian relations is significant, these relations are complicated by the larger context of the war on terror in the Sahel that a special issue of the Journal of Contemporary African Studies edited by E. Ann McDougall in 2007 examines.

In regards to the ongoing civil war in South Sudan, solutions have been elusive and the cost to civilians high. A number of media outlets focus on South Sudan, helping to provide a more complete picture of events in the country: Juba Monitor (published in Juba), South Sudan News Agency (published in the United States), South Sudan Broadcasting Station on YouTube, SouthSudanNation.com, Sudan Tribune (published in Paris), and the New Sudan Vision (published in Canada).

China Global Television Network recently posted this video detailing anti-violence activism by young South Sudanese artists on the CGTN Africa YouTube channel. YouTube in general is an excellent source for news and opinions on South Sudan.

Erik Prince, China, and Frontier Services Group

Erik Prince is a hard man to keep up with. Since relocating overseas to help build the United Arab Emirates’ new security force (composed largely of mercenaries from across Latin America), he has continued to expand his private military business free from US-government interference. China has been the investor most interested in funding this expansion.

This video, posted to YouTube in 2015, profiles Prince’s new company, Frontier Services Group (FSG; their website defaults to Mandarin), which is funded at least in part by capital from Frontier Resource Group. FSG is not just working in Africa—although it did recently ink a deal with the South West State of Somalia to manage a new free zone in the semi-autonomous region. FSG also has its eyes set on Asia. As the company explains on its investor relations page, their “target markets in Africa include Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo. Northwest region focuses on Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Southwest region predominately serves Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia.”

As I discussed in my essay, this has all been cast in the harshest possible light in the United States. This April 2015 editorial cartoon from Nick Anderson of Hearst illustrates well the easy slippage into old stereotypes that Prince’s “defection” has provoked. In the two frames of the cartoon, Prince goes, quite literally, from being a successful patriot to a criminal and a communist. Maden’s novel Blue Warrior is very much a white-supremacist fantasy of what a character like Prince would be like if America were “great again.” And as we move further into the Trump presidency, Erik Prince begins to sound more and more like fictional mercenary Troy Pearce. In a recent CNN interview defending his plan to privatize the war in Afghanistan—a modern East India Company—Trump criticized National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster’s commitment to using US forces to continue the long occupation, referring to McMaster dismissively as a ‘three-star conventional army general.

Thinking beyond Prince, it is important to recognize that FSG is essentially a Chinese company—that happens to have an American mercenary as its chairman—focused on providing security in frontier markets. The company operates based on the formulation of what David Harvey called “neoliberalism with ‘Chinese characteristics’” following Deng Xiaoping. FSG recently announced that it will establish forward-operating bases in Yunnan province and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, helping to contribute to Xi Jinping’s One Belt One Road development strategy. The company has also acquired a 25% share in the International Security and Defense College in Beijing.

The private military business is a growth industry everywhere, it seems. For example, Alleen Brown, Will Parrish, and Alice Speri at The Intercept have published a five-part investigation into the role of private military company TigerSwan in helping to suppress the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock.

In the above video posted to YouTube, Cenk Uygur of the Young Turks draws on Brown, Parrish, and Speri’s work to profile TigerSwan’s role at Standing Rock.

AFRICOM

Near the end of his life, Chalmers Johnson continued to lament the US “empire of bases.” With about 800 military installations in foreign countries, the United States has a significant global footprint. One of these bases is Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, the “primary base of operations for U.S. Africa Command in the Horn of Africa.”

In class, my students and I laugh at the amateurishness of the official videos that AFRICOM posts on its YouTube channel, like this 2016 year in review feature. Then I ask students to reflect that it is young people their age who are doing this work and we read about U.S. Army job 46Q, Public Affairs Specialist and watch a short YouTube video about the specialty. These videos, along with AFRICOM’s 2017 Posture Statement, are ripe for textual analysis by students in courses focused on militarism, imperialism, and communications.

Finally, Camp Lemonnier recently got a new neighbor—a Chinese naval station. This one Chinese outpost has caused much concern in spite of the fact that the United States operates 46 outposts across the continent according to Nick Turse at TomDispatch. Although US participation in the hunt for Joseph Kony—who most people seem to have forgotten about—recently came to an end, the US remains deeply invested in its militarized approach to the continent. Still, China is the one being cast as the “dragon in the bush,” and with the future of US-China relations unclear, it will be interesting to see if the specter of “communist China” and the “yellow peril” is invoked at an increasing frequency—just as Russia has once again been embraced by many Americans as the preeminent enemy of US democracy.

Dwelling over China: Minor Transnationalisms in Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel

Lily Wong

Karen Tei Yamashita published her novel I Hotel in 2010, five years after the physical International Hotel (I-Hotel)—a center for the Asian American movement in the 1960s and 1970s—was revitalized on its original site in the Manilatown–Chinatown section of San Francisco. Rebuilt in 1907 after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the International Hotel was a low-cost residence that housed many Filipino and Chinese migrant workers. A majority of the tenants were bachelors who were unable to own property and form nuclear families because of various US exclusion acts and anti-miscegenation laws.[1] The symbolic value of the I-Hotel—situated at the heart of San Francisco’s ethnic enclaves, under siege during the height of antiwar and Third World liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s—quickly turned the historic building into a site for local activists to organize around racial and spatial justice. Yamashita’s novel reanimates this history of mobilization. Her six-hundred-page novel houses a multitude of intersecting tales about the residents and activists, starting from 1968, when the first eviction notice was handed out, and ending in 1977, when the last occupants were evicted.[2]

In this essay, I focus on how Yamashita reimagines China and Chinese social movements in her narrative to recover a pivotal time in US movement politics (1968–77). Under Yamashita’s pen, “China” becomes a symbolic site through which her characters reassemble historical connections and reanimate political affiliations. The article argues that by dwelling over “China,” Yamashita reengages the dynamism of anti-imperial politics before China’s rise as itself a neoliberal empire. In the act of recollection, the novel reinvents context, reconfigures meaning, and reorients symbolic trajectories. She activates the intervening slash in what David Palumbo-Liu terms “Asian/America,” illuminating the mutually constitutive histories between the United States and China. In so doing, Yamashita configures minor transnational connections: she decenters ideas of the nation-state (be it the United States or China) and ruptures narratives of global capital accumulation in a neoliberal order.

[1] For more on the history of the International Hotel, see Curtis Choy’s documentary The Fall of the I-Hotel (1983)

[2] Podcast of Yamashita reading from her novel I Hotel.

The Crisis of the American Dream: On Going-Abroad Films in Contemporary Chinese Cinema

Yanhong Zhu

Beginning in the 1980s, China witnessed a strong surge of interests among students and workers to go abroad, especially to the United States. This so-called “going abroad fever” has continued steadily into the current decade. Film and television have served as a privileged medium for depicting and representing the “going abroad fever.” Many of the early representative films often demonstrate a strong ambivalence toward the United States, best captured in the hit TV series Beijingers in New York (1993) in which New York is depicted as both heaven and hell.

A new wave of films on the issue of going abroad emerged in 2013, followed by more similarly themed films. The ambivalence seen in the earlier films and TV series is often replaced by an overwhelming sense of disillusionment in many of the recent US-themed films, including, for example, Vicki Zhao’s So Young (2013), Frant Gwo’s My Old Classmate (2014), and Luo Dong’s New York New York (2016). By depicting the United States as a land of false promises and failed dreams, these films not only highlight the crisis of the American Dream, but also reveal the deeply entangled nature of US-China relations: on the one hand, the United States sees China as a threat to its global hegemony; on the other hand, China strives to promote the idea of “peaceful rise” in its foreign policy and in public discourses. Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013) serves as a rebuttal to the “China threat theory” by replacing the false American Dream with the real Chinese Dream.

Set in contemporary China, Xue Xiaolu’s two films Finding Mr. Right (2013) and its sequel Book of Love (2016) explore the new craze for going abroad among China’s expanding middle-class and examine such social phenomena as birth tourism, oversea real estate investment, and the continuing study-abroad craze with a much younger age structure. Focusing much of the narratives on self-discovery and self-transformation as well as the themes of love and family, these films criticize the materialism of contemporary Chinese society and seek to reassert the importance of lasting values like family, love, and trust that far exceed material wealth. Book of love, just like American Dreams in China that attempts to shift from the American Dream to the Chinese Dream, also longs for a return, across the dazzling world of globalization, to home – to China.