The seven essays in this issue are particularly rich in the originality and rigor of each work as well as in the diverse ways in which they engage the interrelated issues of racialization, state power, surveillance and policing, citizenship and identities.

Therese Quinn and Erica Meiners have convened an important and timely forum, “Defiant Memory Work,” which draws on Chicago’s rich history in using cultural forms to foster liberation and engages myriad projects in other sites where artists and activists, particularly from marginalized groups, have used culture to resist erasure and dispossession.

Roderick Ferguson's presidential address takes us to the site of a heterogeneous, mixed population of Native and black people whose relationships to each other and to the land were apprehended by the logics of settler colonialism and racial capitalism. Jodi A. Byrd responds to Ferguson’s address and pushes us to think further about the agency of southeastern American Indian women in the transformation of Indigenous traditions and relationships. Shona N. Jackson turns to the Anglophone Caribbean, where settler colonial logics of land and labor became the basis for Creole Indigeneity and antiblackness.

“Poor Influences and Criminal Locations: Los Angeles’s Skid Row, Multicultural Identities, and Normal Homosexuality”

Nic John Ramos

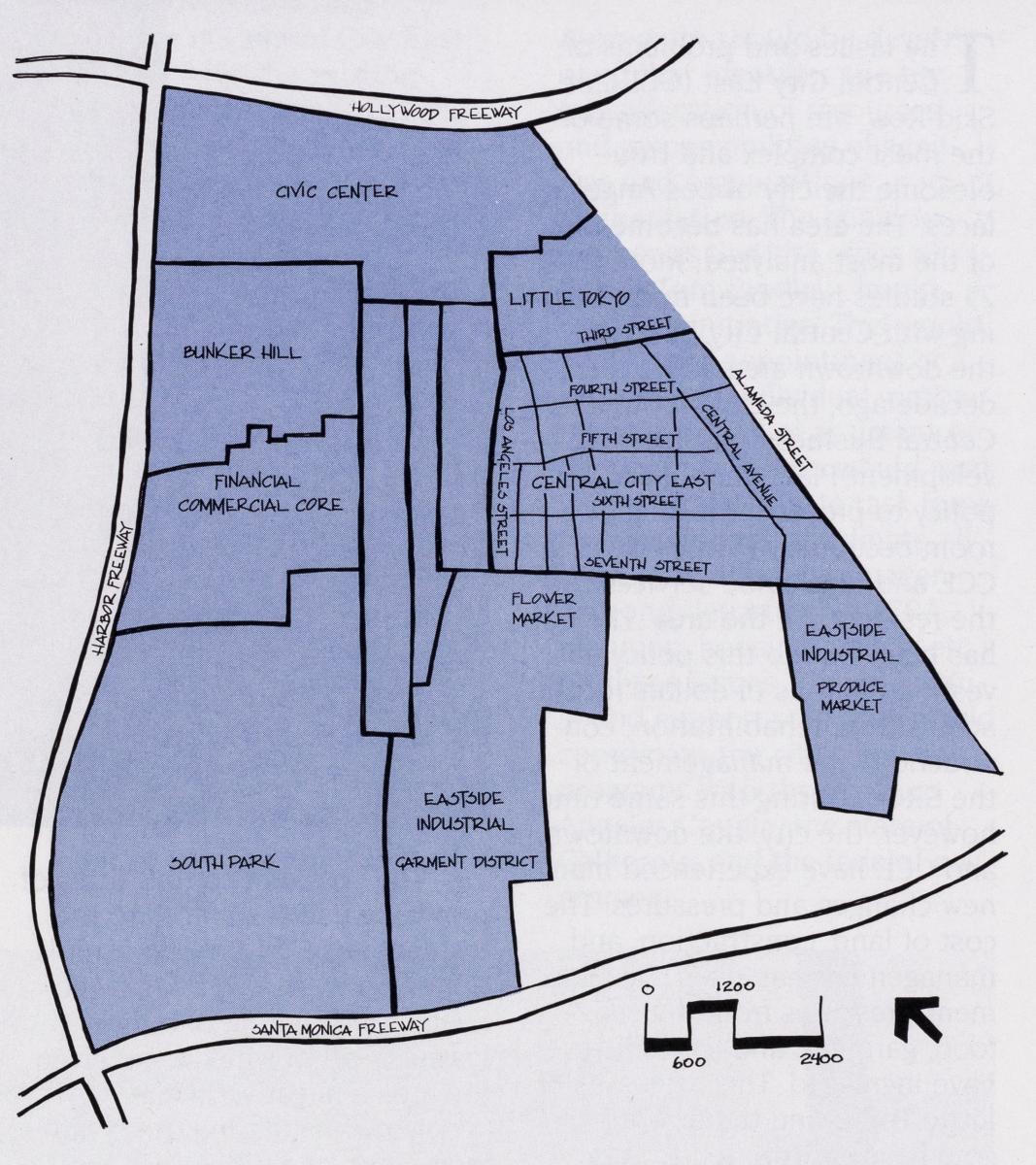

In my essay, I explore the policing of black and brown trans women into a city-ordinance enforced “homeless district” called Skid Row on the eve of the city’s hosting of the 1984 Olympic Games by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). The event was intended by city officials to brand Los Angeles as a cosmopolitan city of multiculturalism, one capable of facilitating new flows of goods, capital, and labor between international markets in an emerging global economy. As I show in the essay, the containment of queer and trans people of color alongside those considered troublesome (such as prostitutes, the homeless, unemployed, and those suffering from addiction and mental illness) inside a consciously made hyperghetto “hidden” in the middle of the city was an important feature of showcasing the productivity and investment potential of the city’s multicultural landscape laying outside skid row during and after the games. Indeed, as David Zirin and Max Felker-Kantor argue, the Los Angeles Olympics transpired over just sixteen days in 1984 but the city continued to police its streets as if it never ended – a fact that no doubt has contributed to the expansion of carceral institutions in California and the United States.

Rather than attribute the rise in policing solely to rising white conservatism, I argue the production of a modern skid row in Los Angeles can be understood, in part, as also a product of the ascension of civil rights and gay rights activists into citywide and local positions of power. By 1973, a new “multicultural” coalition of city officials, led by Mayor Tom Bradley, found themselves balancing their own interests in forwarding new positive ideas of race and homosexuality against the effects of deinstitutionalization and deindustrialization in the late 1960s and 70s.

My essay in AQ is meant as an accompaniment to another article I recently published in the Journal of History of Medicine and Allied Sciences titled, “Pathologizing the Crisis: Psychiatry, Policing, and Racial Liberalism in the Long Community Mental Health Movement,” which explains the discursive contributions of mid-1960s and early-1970s psychiatry to broken windows policing, an approach to policing that helps explain the rise of prisons in the U.S and new policing strategies worldwide. Whereas Pathologizing the Crisis explains how broken windows policing was applied outside of skid row to detain known and suspected criminals in prisons, Poor Influences and Criminal Locations demonstrates how these logics were suspended in order to deposit citizens considered “troublesome” but not immediately detainable by penal or mental health law into skid row. Leaning thus on new normalizations of race and homosexuality emanating from local community mental health advocates and black and gay pride movements, the city’s new power brokers sought to produce black and gay districts laying outside skid row (in South and West Los Angeles) as equal to white suburbs by policing black and homosexual subjects who failed to meet new ascriptions of normal racial and sexual standards into a modern skid row.

Teaching Poor Influences and Criminal Locations

As the Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow of Race in Science and Medicine at Brown University, I had the opportunity to teach the historical arc that precedes and proceeds the content of my essay in a course I led called Race, Sexuality, and Mental Disability History [Insert link here] in the Department of Africana Studies. The course traces the rise of psychiatric racism in the United States in the late nineteenth century and the efforts to de-pathologize race and homosexuality starting in the 1920s and 1930s. Most histories of race and homosexuality within psychiatry rightly focus on the role race and sexuality played in the asylum and/or state hospital, which served as the pre-eminent site of psychiatric thinking for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. My own research and writing, however, suggests that too narrow of a focus on the state hospital ignores the partnerships mental health professionals forged with police departments, educators, social workers, and community activists working outside state hospitals after Emancipation and territorial expansion in the 1880s and after the popularization of psychoanalysis in the 1920s and 1930s.

I found the documentaries Bridging the Divide, by Lyn Goldfarb and Alison Sotomayor and Changing Our Minds by Richard Schmiechen, useful to contextualize the status of race and homosexuality in society and psychiatry up until and during the depathologization period of the 1960s and 1970s. As many of my students often note, these movements often do not appear as explicitly psychiatric in nature and are often tagged under the banner of black and gay pride movements. My essay uncovers that black psychiatrists helped constitute and amplify black pride discourse through their direct involvement in a vibrant black arts scene that still persists in Los Angeles today.

I highlight black psychiatry’s contribution to social movements through an influential yet under-appreciated black psychiatrist named J. Alfred Cannon, who pioneered work at UCLA before moving on to Chair Psychiatry at Drew Medical School. Cannon co-founded the Inner City Cultural Center and the Mafundi Institute in the late 1960s, two pioneering art centers focused on fostering actors and artists of color for work in Hollywood and elsewhere. Cannon, however, was not the only black psychiatrist to translate new racial theories of mental wellness into popular culture form. In fact, Cannon’s tenure as the Chair of Psychiatry at King-Drew Medical Center was succeeded by Chester Pierce, a senior advisor for Sesame Street. Cannon’s orbit of colleagues also included Alvin Pouissant, who served as a well-known advisor for the Cosby Show and likely worked alongside Cannon while at UCLA Medical School. As Pouissant explains, it was important to eliminate negative representations of blackness and replace with them positive ideas of race. While there are many works educators can use to contextualize this period, I have found the last episode of The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross as a piece that helps account for the rise of black pride and some of the criticism and shortcomings as black culture and life changed in the 1980s.

In the essay I also highlight the contributions that mental health professionals made to the gay pride movement, a corollary movement that arose on the heels of black pride. I pay particular attention to Evelyn Hooker, a homophile psychologist at UCLA. Readers and educators interested in using primary documents in their lesson plans can access a recorded lecture of Hooker speaking at the ONE Archives Foundation, one of the largest repositories of LGBT archival material in the world. While much of her work has been celebrated as universally good for all homosexuals, her lecture (beginning at 14:53) reveals that she adamantly believed that some forms of homosexuality (such as those that signaled to her gender confusion, shame, and masochism) should still be prevented because they were “destructive” developmental maladjustments created in childhood.

All this explains the hyper-policing of black and brown trans people in an era generally remembered as a moment of progress for people of color and gay people. One does not have to go far to find the voices of trans activists contesting this narrative as it unfolded. Sylvia Rivera, for instance, noted that the gay pride movement in New York moved away from trans rights in an attempt to define and win “gay rights” bill and, in so doing, also moved gay activist objectives farther away from anti-prison and anti-police organizing. There have been recent attempts to recognize and reconcile this history – the most notable being the proposed construction of memorials to Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson near the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village, an area which has long been recognized as a gay neighborhood.

As I have suggested in my essay, however, not all gay neighborhoods get remembered as such. Cities like Los Angeles policed out some queer and trans citizens into neighborhoods meant to contain what some call a “permanent underclass.” The recent triumph of some activists in San Francisco to re-name parts of the Tenderloin as Compton’s District as the “the first legally recognized transgendered cultural district” reveal that Los Angeles’ method of policing was not exceptional but shared amongst other global cities. For sure, the effect of trans discrimination and sex worker discrimination in social service agencies help account for the appearance of health clinics such as St. James Infirmary in San Francisco and the Audre Lorde Project, which specifically gear their services towards helping trans and queer people of color.

Towards the end of my essay I argue that the policing and discrimination of trans and queer people of color is likely to become more acute given that the inner-city spaces these populations have been policed into, like Skid Row in Los Angeles and the Tenderloin/Compton’s District in San Francisco, are now the most expensive pieces of real estate in their cities. Gentrification and displacement threatens not only those living downtown but also the near downtown neighborhoods that surround the downtown core. These neighborhoods now include, in fact, the black and gay neighborhoods that Tom Bradley and his allies sought to preserve as havens for racial and sexual minorities.

For a better understanding of skid row and homelessness in Los Angeles today, I suggest looking to the Los Angeles Community Action Network. The views of these activists can be contrasted with how their voices appear (or do not appear) in a 2018 PBS News Hour segment and a 2015 article from the New York Times. As those who read my essay can surmise from current takes on skid row from city officials and the media, the rhetoric to relocate skid row’s citizens under the auspices of being “humane” and “caring” ironically reproduce the same rhetoric that policed the same citizens into a modern skid row to begin with.