This issue goes to press in the wake of the police shootings of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, followed by the shooting of police officers during the peaceful protest led by Black Lives Matter in Dallas, Texas. The shocking events remind us of the continued need for grounded understanding of the structures of racism, violence, and state power and clear visions for action and dialogue. Many of the essays included here address themes that are critical to these issues.

Hope in Dystopian Times: In the Heart of the Valley of Love and the Limits of Cold War Racial Liberal Ocularcentrism

Pacharee Sudhinaraset

This essay brings together three moments of conflagration and crisis—the 1960s, 1992, and 2014—in relationship to the politics of visuality and genre to explore the afterlife and counterlives of US Cold War racial politics. Scholarship on the Cold War has noted a marked interest by the US state to institutionalize ideologies of racial liberalism in order to break with formalized white supremacy within a geopolitical struggle against communism. In particular, addressing the insurrections of the 1960s was seen as key to better position the US as a leading nation in defending social freedom. Situating Cynthia Kadohata’s 1992 novel In the Heart of the Valley of Love alongside the 1968 Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission Report), I approach the report as a dystopian text that cultivated an antiracist mode of perception through an affect of fear that fixed acts of “seeing” race through bodily difference and urban space. Kadohata’s In the Heart, I argue, provides a counter-dystopic vision, or critical dystopia, that not only critiques racial liberalism’s regime of perception, but also provides alternative notions of perception to invigorate the vexed politics of visuality.

I am currently teaching an undergraduate course on women of color feminism, literature, and the politics of visuality. Daily, my students remind me how important it is to study, teach, and unpack our inherited regimes of racialized, sexual, and gendered perception. They affirm how imperative it is to name, question, and imagine alternatives to how we take in the world through sight, sound, movement, and feeling in relationship to larger institutional structures and epistemic shifts. By entering the Rodney King beating and the murders of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice through the Kerner Commission Report and In the Heart I hope to contribute to this project of naming, questioning, and searching for alternatives to seemingly totalizing visions of futurity and hope. Mirroring the organizational divisions of my essay, I hope that the following links supplement and provide context and fodder for further exploration within and beyond the classroom.

Beginning in the year 2052, my essay establishes the centrality of women of color speculative writing practices in relationship to the 1960s, 1990s, and 2010s. Although not comprehensive, this bibliography on women of color speculative fiction and Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown’s anthology are useful resources to begin a reading list on women of color speculative fiction.

This set of papers provides interesting supplemental materials to the Kerner Commission Report. Here is the link to William Petersen’s 1966 New York Times article on Japanese-Americans as model minority.

To help contextualize the Rodney King beating, George Holliday’s video can be readily found on YouTube, but I have decided instead to include links to Anna Deavere Smith’s one-woman play Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 and Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Christine Choy and Elaine Kim’s Sa-I-Gu. These films provide interesting counter-aesthetics and visual projects to grapple with the events around King’s beating and the Los Angeles uprising. President George Bush’s response to the 1992 riots and his language of “law and order” also provides a useful text for exploring the discourse and visions of the state.

My essay ends with a call to understand the 2014 shootings beyond the narrow visions and terms of the state. In the months following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by Officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014, and days after the subsequent Missouri grand jury decision not to indict Wilson on November 14, 2014, protests and riots ensued and headlines emerged that demanded a reconsideration of the Kerner Report. According to The Daily Beast, America has forgotten the lessons of the Kerner Report and “needs to learn it again.” For The Huffington Post, civil rights lawyer James Meyerson proposed that President Obama appoint a Commission, chaired by Jimmy Carter and George W. Bush, that included “distinguished and diverse members” such as Sandra Day O’Connor, Janet Reno, Henry Cisneros, and Oprah Winfrey, to “courageously face our past and our present in order to plot our course forward.” Almost six decades after the uprisings of the 1960s, faith in state-sanctioned resolutions remain and hope is still imagined through increased surveillance and black and white reconciliation.

On the other hand the Black Lives Matter Campaign, founded by black, queer, immigrant activists such as Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, have seized upon different spaces and cross-racial struggle to invigorate social movement. Educators such as Frank Roberts have responded to this moment through the pedagogical form of the #blacklivesmatter syllabus. Cross-racial alliances have moved beyond the black-white binary and against the terms of the state as they have been reimagined through the Asian American model minority mutiny (please see here, here, and here for examples), black-Palestinian solidarity (see here, here, here, and here), and the Black Lives Matter Network support for the indigenous water protectors at Standing Rock.

Mapping Black Laughter, Mapping Black Movement: Ralph Ellison’s New York Essays

Cynthia Dobbs

To honor the complexity of Ellison’s vision and subject matter in this essay, I found myself travelling down multiple disciplinary routes: from archival research in the Ralph Ellison papers at the Library of Congress, to histories of African American migration, to rhetorical and psychoanalytic theories of humor and laughter, to cultural geography, and, oddly enough, to the history of Esquire magazine. These routes intersected in surprising ways and led into unanticipated territories for continued research. Here are a few signposts for further exploration:

- Housed in the Library of Congress, American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers Project, 1936-1940, a collection of over 2,900 digitized documents gathered by the hundreds of writers employed by the Work Progress Administration’s Federal Writers Project, is an invaluable resource for teacher-scholars of twentieth-century American history. The Federal Writers Project employed such prominent African American authors as Sterling Brown, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, and Richard Wright. Among the collection’s ethnographic essays, you can find Ellison's 1938 interview of Great Migration migrant Leo Gurley. Ellison interviewed Gurley on Lenox Avenue in Harlem, where Gurley recounts tales of a man back in South Carolina who “makes hisself invisible” in order to escape Jim Crow police.

- The Schomburg Center for the Study of Black Culture, an embarrassment of riches for any scholar, houses more of Ralph Ellison’s reportorial writing from this period, including his historical sketches of prominent African American New Yorkers, beginning in the 18th century. These sketches include brief biographies of "New York's first Negro poet" Jupiter Hammon, whose “position as a slave of a Long Island family seems to have been small hindrance to his literary activity,” and of Katy Ferguson, who was born into slavery when her enslaved mother was en route to New York in 1774, later adopted by abolitionists, and finally emerged as a major philanthropist for impoverished children of all races in New York City.

- While my essay explores Ellison’s personal memories of negotiating the perilous racialized landscape in New York City in 1936 “without a map,” African Americans traveling through American geographies in the 1930’s through 1960’s could turn to The Green Book. A travel guide aimed at African Americans, the “Green Book” was first published by Victor Green in 1936 to provide “the Negro traveller information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.” The first edition focused on New York solely, but the guide was so popular that the following year, Green expanded its geographic range to include most of the United States. For a brief audio history of the Green Book, go to NPR on the Green Book.

- In “Harlem is Nowhere,” Ellison describes an African American mastery of “those techniques of survival to which Faulkner refers as ‘endurance’ and an ease of movement within explosive situations which makes Hemingway’s definition of courage, ‘grace under pressure,’ appear as mere swagger.” For several instantiations of such subversive Black movement, absorb Beyonce’s Lemonade and Janelle Monáe’s Tightrope.

“Parasites of Government”: Racial Antistatism and Representations of Public Employees amid the Great Recession”

Daniel Martinez HoSang and Joseph Lowndes

Our article examines cultural representations of race and “parasitism” used in attacks against public employees during the Great Recession. Beginning in 2009, a chorus of critics charged that unionized public employees were becoming, in the words of Rush Limbaugh, “parasites of government,” dependent subjects that consumed tax dollars and productive labor to subsidize a profligate lifestyle. Such narratives of parasitism have long been racialized and gendered; subjects marked as “welfare queens” and “illegal aliens” among others have been similarly condemned as freeloaders who feed off the labor of hard-working (white) taxpayers.

By analyzing a series of cultural representations--political cartoons, television shows, political advertisements and speeches—we demonstrate how constructions of parasitism have become transposed onto white workers, including emergency workers and teachers, who have traditionally been exempt from such charges.

For example, the California chapter of the conservative political advocacy group known as Americans for Prosperity produced this segment titled “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous on a Government Pension.” The segment was part of a broader effort to depict public employees as parasitic and extravagant in a moment of budget crisis and austerity. The effort caught the attention of producers at the syndicated show Inside Edition which produced a 2012 segment featuring an AFP representative alleging that Orange County, California lifeguards pocketed hundreds of thousands of dollars each year in taxpayer-funded salaries and benefits for frolicking on the beach.

These attacks reflect the most recent development of an anti-statist politics that had historically assailed the redistributive state through its association with racialized dependents. As these segments reveal, certain white beneficiaries of state action have been absorbed within the same cultural and political logic. In other words, during current the age of inequality, the state-sponsored economic entitlements often described as ‘affirmative action for whites’ that had been promised since the New Deal is no longer guaranteed.

We use the term “racial transposition” to describe a process through which the meaning, valence and signification of race can be transferred from one context, group, or setting to another. This process of transposition is evident in a 2010 skit titled “2010 Public Employee of the Year Awards from the NBC television show Saturday Night Live that we analyze at length. The skit, features actress Gabourney Sidibe (star of the 2009 film Precious), cast as a St. Louis Department of Motor Vehicles employee named “Markeesha Odom.” The narrator explains she has been “twice named Missouri’s ‘Surliest and Least Cooperative’ state employee.” Sidibe scowls at the camera, hand on hip, lips pursed. The other award finalists are two white men who revel in do-nothing government jobs, limitless overtime, and farcical work rules secured by a union contract. Here, the viewers are first introduced to the logic of parasitism through a black woman, whose purported laziness and belligerence are familiar in the context of a long history of such representations. These claims are then extended or transposed to two white male characters, cognizable in part through their association with Sidibe’s character.

In the final part of the article, we examine the strategies and representations used by public sector unions to contest the charges of parasitism they increasingly faced. We analyze a series of representations used by unions and their allies to defeat an Ohio ballot measure in 2011 known as Issue 2 that would have removed a broad range of protections and rights for many state and local government workers. The statewide campaign led by a coalition called We Are Ohio countered the charges of parasitism by portraying public employees as producerist heroes, drawing on racialized and gendered representations of teachers, “first responders” and health care workers in ads such as “Nurse,” “Everyday Heroes,” and “Protect and Serve.”

While the coalition defeated Issue 2 on Election Day, we argue that by valorizing white heroism in this way, it constricts the grounds on which others can make claims to the public wage and pubic services, and naturalizing and reproducing the producer/parasite distinction.

Energy Slaves: Carbon Technologies, Climate Change, and the Stratified History of the Fossil Economy

Bob Johnson

Caption: Rastus Robot, A Mechanical Slave (Westinghouse 1930).

Photo originally appeared on Jim Linderman’s website Dull Tool Dim Bulb.

ARTICLE SUMMARY

89 ENERGY SLAVES! That is the amount of labor power, we are told, that Americans and Canadians rely on per person to support their standard of living today.[i]

The term energy slave refers to the work we derive from combusting fossil fuels. It evokes the mechanical labor (i.e. tractors, cars, container ships, and washing machines) that supplements the physical labor we can get from living bodies – from draft horses, oxen, and people. Most of the time we simply refer to horsepower when we think of energy converted into work. We say, for example, that the engine in my Subaru Outback can generate 256 horsepower. But it has also been conventional to speak, at various times, and in certain political contexts, in human referents – of mechanical slaves, of electric servants, and, now today, of energy slaves. The photograph above of “Rastus Robot” is simply one arresting – and disturbing – effort to materialize that analogy by giving to this energy a historicized body that is racialized, gendered, and classed.

My essay in AQ reconstructs the genealogy of this term. But rather than take the term at its face value, it examines the distortions that the term produces. To be more specific, this essay contends that the trope of energy as slave produces certain factual and ethical errors that bury the deep social inequalities of energy consumption in a narrative of universal emancipation, by tur, that turn us away from the increased exploitation of certain working bodies in the fossil economy, and that misrepresent for us the actual ecological functions (beyond fueling machines) that fossil fuels play in today’s climate crisis.

TEACHING IN THE ENERGY HUMANITIES

This essay takes shape within the emerging field of the energy humanities. That field of study is part of the academy’s cultural response to climate change. The energy humanities seeks to tie material matters of technology, infrastructure, resources, and climate change to issues of ethics, social equity, aesthetics, and creativity that concern us. In its best practices, its advocates help us to bridge the vast cultural gap that has developed over the last century among the natural sciences, engineering, and the humanities and that impedes a healthy and holistic climate politics.

The following is a short list of recommended texts for anyone interested in catching up on recent literature in the energy humanities.

Most scholars seem to start with:

- Stephanie Lemenager, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (2013)

A second canonical text has become:

- Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (2013)

After that a number of recent works explicitly bear down on the field of American Studies:

- Imre Szeman, Jennifer Wenzel, and Patricia Yaegar, Fueling Cultures: 101 Words for Energy and Environment (2017)

- Matthew Huber, Life Blood: Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital (2013)

- Ross Barrett and Daniel Worden, Oil Culture (2014)

- Bob Johnson, Carbon Nation: Fossil Fuels in the Making of American Culture (2014)

- Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming (2016)

And some older works provide important groundwork and context:

- Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918 (1983)

- Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (1990)

- David Nye, Consuming Power: A Social History of American Energies (1999)

ACTIVITY 1: LABORING IN THE AGE OF FOSSIL FUELS

- One teaching activity that can be tied to this article concerns what we might call the energy imaginary: that is, the language and images we have for representing the meaning of machines, bodies, and fossil fuels today.

- A key point that I develop in my AQ essay is that the terms labor and work underwent a major definitional shift during the transition to a fossil-fueled and mechanized world. The changing meaning of work registered in American popular culture (in newspapers, articles, advertisements, and films) where the rhetoric of mechanical slaves became central to modernity’s self-conception, and it was given professional form in scientific circles as physiologists, physicists, and engineers developed a discourse of thermodynamics that put human bodies, machines, and fuel calories (whether from a bagel or a chunk of coal) into the same conceptual basket.

- To help students recover the uncanny nature of this shift in the meaning and practice of work, it can be fun to have them browse through images of humanoid robots and historical advertisements of mechanical servants. These can help them to see the weird shifts that were occurring as modern bodies became attached to, displaced by, and subjugated to energy technologies.

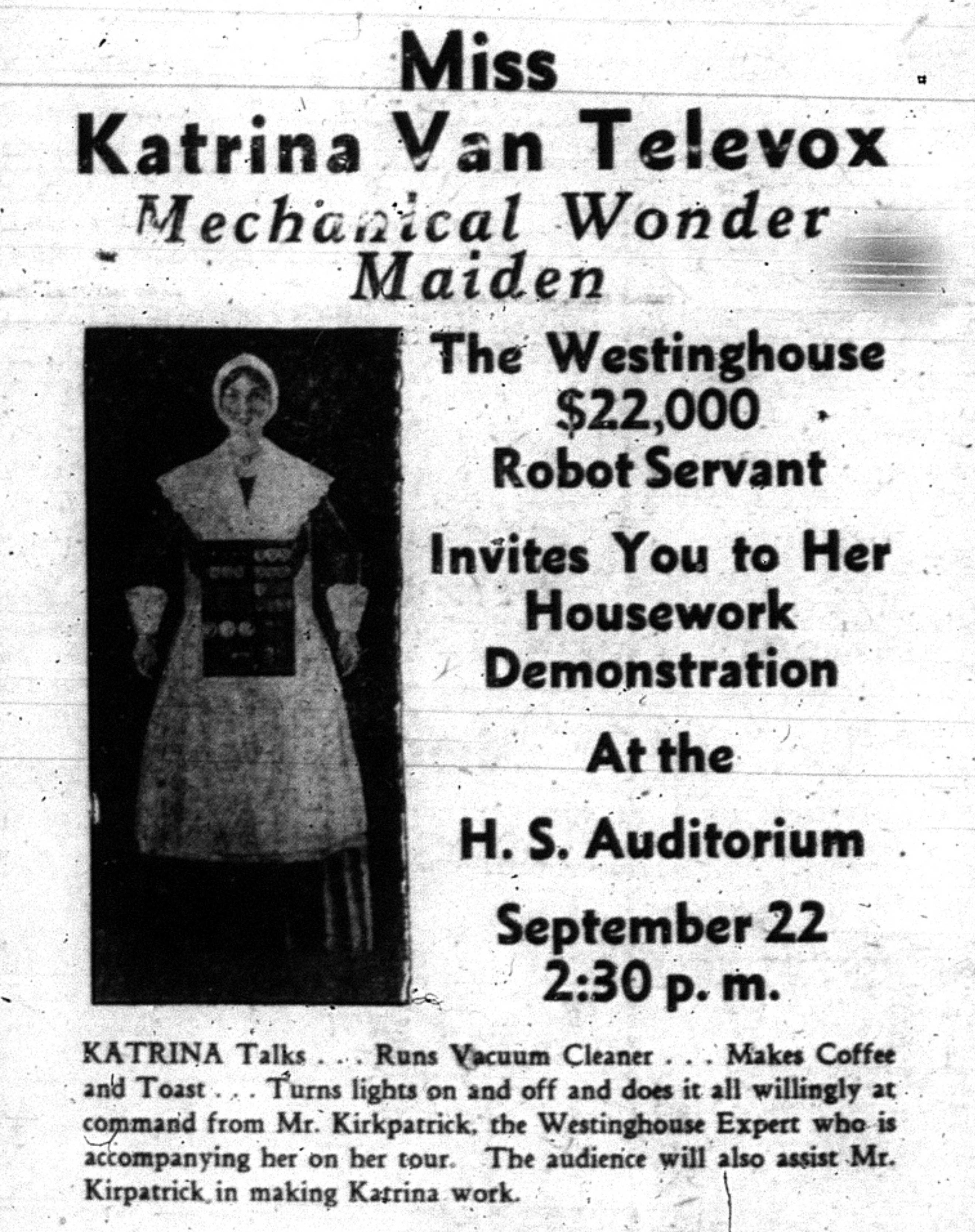

Caption: Katrina Van Televox

“The Mechanical Girl [who]… always does exactly what you tell her.”

Some questions to ask are:

- What was meant by a “mechanical servant” or “electric slave”?

- What was the historical context that this metaphor took shape in?

- To what extent were these “mechanical slaves” portrayed in racial, class, or gendered terms?

- Does the metaphor of the mechanical slave accurately portray the role of energy and technology in modern life?

- What does this metaphor conceal?

Credit: Morning Herald, Hagerstown (1931) under Fair Use.

I originally came across Rastus Robot at the popular tech websites Paleofuture.com and Cyberneticzoo.com. Browse through these fun sites for examples of the discourse that surrounded these so-called mechanical slaves.

ACTIVITY 2: EMBODYING ENERGY: ENBRIDGE’S “LIFE TAKES ENERGY” CAMPAIGN

A second teaching activity that can be tied to this article concerns energy industry propaganda.

Energy giants, such as BP, GE, and Enbridge, have tried to demonstrate going back to the 1920s and 1930s how deeply invested we are in fossil fuels – how our values and culture are propped up by them. They have sold us on a certain vision of energy consumption that is tied to overly simplistic beliefs in human emancipation, consumer comforts, and nationalistic narratives of empowerment and freedom.

Students might start by taking a look at industry films like the American Petroleum Institute’s Destination Earth (1956) or contemporary advertisements like GE’s Model Miners (2008) to see how our investment in consuming fossil fuels has been portrayed in ideological ways that ignore the complex environmental and social realities that surround them.

One particularly persistent move, as my article shows, has been to equate energy with emancipating the human body from labor. That metaphor has a deep and problematic history, of course.

Let us take, for example, the following Enbridge Advertisement from the company’s “Life Takes Energy” campaign. My attention was brought to this weird little advertisement by the literary theorist Imre Szeman, founder of the After Oil School and the Petrocultures Conference. It fits within the longer trajectory of energy propaganda that equates fossil fuel consumption to the freedom from labor. Here we see the world class cyclist, Robert Forstemann, try to generate enough electricity to light up a piece of toast. It turns out he has a hard time of it.

Caption: Enbridge “Life Takes Energy Campaign” (ca. 2015)

Questions to ask:

- What is Enbridge trying to sell in this advertisement?

- What is the relationship between energy and the body in this video?

What is concealed or misrepresented about our energy dependencies here?

To tie this back to the task of climate change: students might be asked to think about:

- Externalities: What is the genealogy of the fuel that they used today? How did it enter their lives? Where did it come from? Whose lives might it have touched along the way? What type of ecological costs likely came with its consumption? Did this fuel serve as a source of emancipation, of destruction, or of something else?

- Disparities: What do they know about the disparities in today’s fossil economy (where Americans consume about 53 barrels of oil a person each year and Bangladeshi’s consume on the average considerably less than one barrel)? Is the fossil economy a space of opportunity or injury? What would a healthy energy transition look like that would answer to the environmental and social costs and benefits of the current fossil economy?

Bob Johnson is Professor of History at National University in La Jolla. He is author of Carbon Nation: Fossil Fuels in the Making of American Culture (UP Kansas 2014) and various essays on energy, politics, poetics, and race. At http://www.carbonchronicles.org.

[i] Nikforuk, The Energy of Slaves: Oil and the New Servitude (2012), 65.

The National Museum of American History's American Enterprise Exhibit and the Value of Structurally Sound History

Brent Cebul

Recent scholarly interest in the history of American business and capitalism has reached the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “American Enterprise,” the museum’s newest permanent exhibit, anchors the 45,000 square foot “Innovation Wing,” which also includes smaller exhibits on currency and “Places of Invention,” showcasing hotspots of entrepreneurialism and innovation. “American Enterprise” is the museum’s sole exhibit spanning the full sweep of American history, and it is a remarkable achievement of historical inclusivity. Particularly successful are interactive installations that invite visitors to dig into business practices, such as the business of slavery. Yet, too often the exhibit’s inclusivity comes without curators’ providing much of a sense of historical scale, power relations, or political and economic structures. This is by design. In the wake of the Congressional imbroglio that followed the Enola Gay exhibit controversy in the 1990s, curators made a tactical decision to deemphasize their authorial voices when framing exhibits. As David Allison, the museum’s associate director for curatorial affairs puts it, curators aim not to “have some message to preach, but” to give visitors “an environment in which you can explore and find your own meaning.”[1] This approach sometimes handcuffs curators, particularly when it comes to explicating the history of economic power, on the one hand, and, on the other, locating the capital, credit, and debt at the heart of capitalism. It would be naïve to imagine the Congress we are blessed with today delivering curators of national memory adequate funding and autonomy. Until it does, however, the crown jewels of American public history will continue to be beholden to private donors. The Innovation Wing’s renovation ultimately cost a total of $63 million, $43 million of which was donated by companies such as Mars, Monsanto, and Motorola, each of which made it into the exhibit. For those who cannot make it to Washington, D.C., “American Enterprise” has a very thorough website including links to all of its interactive material, much of which would offer worthwhile introductions to aspects of the history of business in a variety of classroom settings.

[1] Sadie Dingfelder, “The National Museum of American History’s new innovation wing chronicles American capitalism,” Washington Post, June 30, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/express/wp/2015/06/30/the-national-museum-of-american-historys-new-innovation-wing-chronicles-american-capitalism/.

Hamilton's America: An Unfinished Symphony with a Stutter (Beat)

Ariel Nereson

“Hamilton’s America: An Unfinished Symphony with a Stutter (Beat),” a review essay of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical theater phenomenon, went to press as the conversation surrounding its innovations and critical reception continued robustly in popular and scholarly venues. The musical also opened in Chicago and announced plans to do so in London as well. When this essay appears, most of the original cast in the principal roles will have departed, and the Ham4Ham ticket line performances described in the essay stopped on August 31, 2016. Fans have archived the performances. A major resource for those interested in the show’s generation, performance, and reception has been released with the original cast, and I point the reader to PBS’s “Hamilton’s America: A Documentary Film.” Additionally, The Hamilton Mixtape, an album of remixes of the original songs that features popular artists, many of whom, like Busta Rhymes, inspired Miranda’s compositions, will be released on December 2, 2016 and will no doubt be an essential companion to the original Broadway cast recording. The Broadway production continues its involvement with current U.S. politics, with Manuel returning in the title role for a special performance fundraiser for Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton.